Editor’s Note: CMTS is committed to giving accurate, accessible information related to Mark Twain, his literature, his circle, and his world. These resource pages have been written by Mark Twain scholars, often times experts in the particular field. These are meant to be reliable, efficient resources for teachers, students, enthusiasts, and the general public.

If you are a scholar who is interested in creating and adding a Mark Twain Studies information page to our growing collection, please contact Director Joseph Lemak (jl****@****ra.edu).

About the Author

Kerry Driscoll, Professor of English Emerita at the University of Saint Joseph (West Hartford, CT) is currently Associate Editor at the Mark Twain Papers and Project at the University of California, Berkeley. A long-time Twain scholar, she is the author of Mark Twain among the Indians and Other Indigenous Peoples (University of California Press, 2018), the first book-length study of the writer’s evolving views regarding the aboriginal inhabitants of North America and Australasia, and his deeply conflicted representations of them in fiction, newspaper sketches, and speeches. She is past president of the Mark Twain Circle of America as well as a contributing editor to its journal, the Mark Twain Annual. She served on the Mark Twain House and Museum’s Board of Trustees from 2017-23, and is currently a member of their honorary Advisory Council. In 2022, she received the Louis J. Budd award for distinguished scholarship from the Mark Twain Circle of America in recognition of her groundbreaking research.

Professor Driscoll has participated in a number of CMTS events and given numerous lectures, including:

- Kerry Driscoll, Ann Ryan, and Matt Seybold, “Beyond the White Suit: Mark Twain in the Twenty-First Century” (October 16, 2025 – Quarry Farm First Floor Library)

- Kerry Driscoll, “A Delicate Balance: Work and Play in Mark Twain’s Creative Process” (October 15, 2025 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Kerry Driscoll, “‘Talking is the thing’: Mark Twain’s Bold Experiment in Empowering Women’s Voices” (August 4, 2022 – Elmira College Campus)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain’s Masculinist Fantasy of The West” (October 2, 2021 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain and the American Indian” (July 11, 2018 – The Park Church)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain, The Maori, and The Mystery of Livy’s Jade Pendant” (October 1, 2014 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Kerry Driscoll, “‘Eating Indians for Breakfast’: Racial Ambivalence and American Identity in The Innocents Abroad” (October 21, 1998 – Quarry Farm)

- Kerry Driscoll, “A Tramp Abroad: Mark Twain in Heidelberg” (March 28, 1990 – Quarry Farm)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain and the American Indian” (1986 – Quarry Farm Barn)

“The Noble Red Man”

Published in the September 1870 issue of Galaxy magazine, “The Noble Red Man” is without question, the harshest depiction of Indians Mark Twain produced over the course of his long career. The circumstances that prompted the sketch’s composition, however, along with the author’s reasons for choosing to publish it in a New York literary periodical, have long been misunderstood. On first glance, the venom that permeates the piece is perplexing. It was written neither during a time of war nor in the immediate aftermath of a horrific massacre that inflamed popular anti-Indian sentiment, such as the Santee Sioux Uprising of 1862; indeed, Twain’s invective runs counter to the assimilationist goals of the peace policy spearheaded by President Ulysses S. Grant. The sketch is nonetheless a highly topical piece, a vitriolic response to a very different kind of event—the Eastern media’s effusive coverage of the June 1870 visit of two separate Sioux delegations—one led by the Brulé chief Spotted Tail, the other by Oglala leader Red Cloud—to Washington, DC to discuss the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty, signed two years earlier.

Contemporary newspaper reports of the Lakota leaders’ historic visit in the Washington Star, Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, and New York Times (as well as the New York Herald, Standard, and Evening Post) depict the Indians in lofty, idealized terms. Article after article emphasizes their imposing physical appearance and striking manner of dress, their “natural” eloquence, and innate dignity—in other words, the very same traits that constitute the basis of Twain’s attack in “The Noble Red Man.” While skeptics might dismiss this similarity as a coincidence, the writer’s personal reading habits, abiding interest in current events, and professional responsibilities as editor and co-owner of the Buffalo Express virtually assure his awareness of the sentimental rhetoric used in describing Red Cloud and Spotted Tail. Moreover, it is likely that this imagery—rather than the iconic fictional figures of Uncas and Chingachgook in James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans—represents the underlying inspiration for the sketch. According to Alan Gribben’s reconstruction of Twain’s library, he regularly read a number of New York dailies over the course of his career; in addition to the Times, Clemens claimed in 1888 that the Evening Post was his “favorite paper,” and stated in 1895 that he “couldn’t do without” the New York Herald. [i] But even if the extensive reports of the Lakotas’ Eastern sojourn somehow eluded him in these various metropolitan publications, the Buffalo Express reprinted—via telegraph—articles on this topic from both the Times and Tribune throughout the month of June.

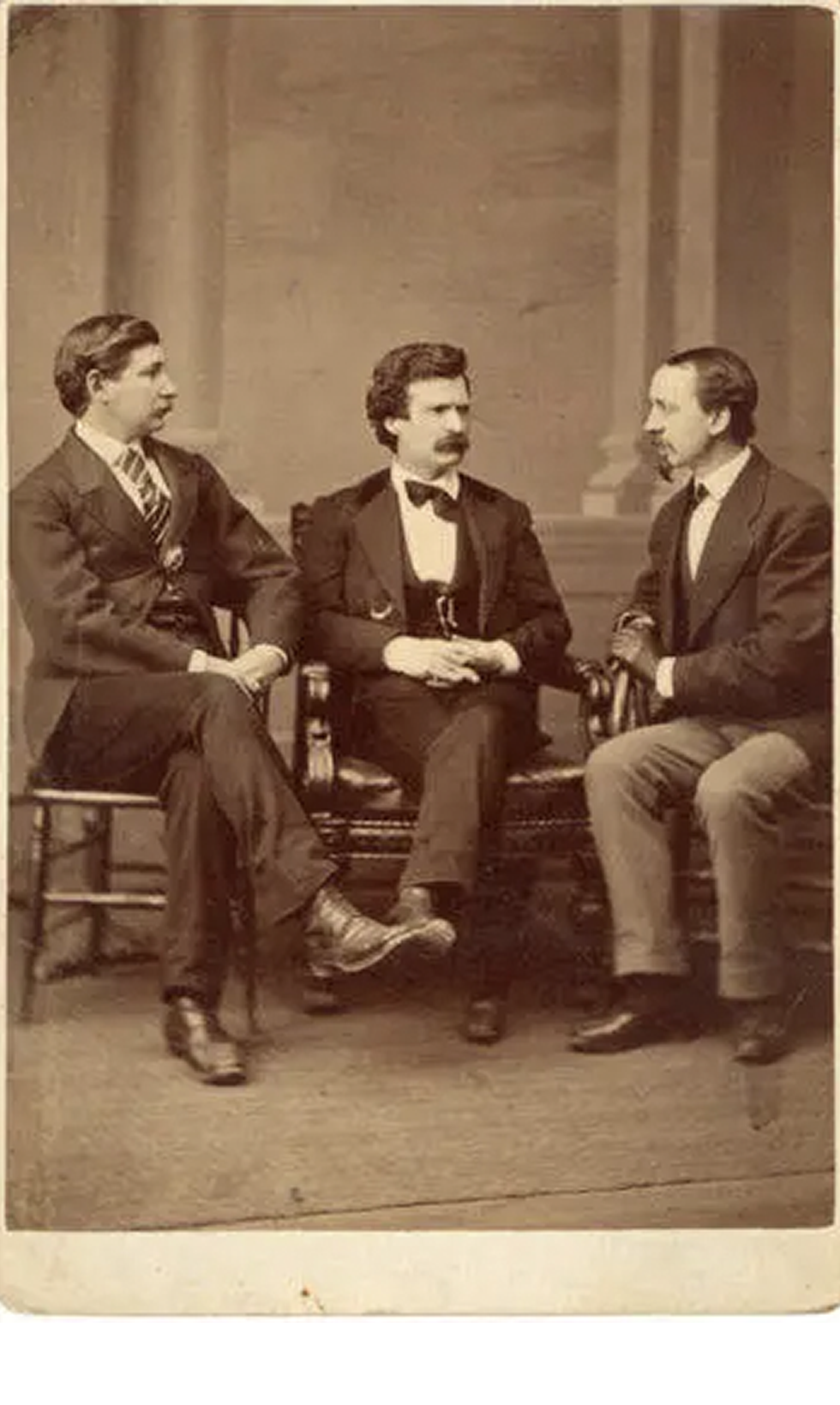

Photo taken in 1871 on a lobbying trip to Washington D.C. George Alfred Townsend, journalist (left); Mark Twain (center); David Gray, editor of the Buffalo Courier (right).

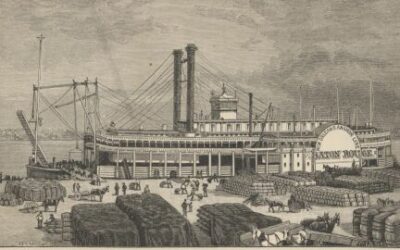

Because Red Cloud steadfastly refused to be photographed throughout his 1870 visit to Washington, print journalism—the daily accounts of his appearance and demeanor published in the New York Times and New York Tribune, among others—offers the only documentation of his stay. These articles were then used by artists to create the highly-romanticized images published in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in late June and early July. On June 18th, for example, the day after Red Cloud’s delegation boarded a west-bound train in New York City for their long trek home, Harper’s Weekly featured an iconic engraving by staff artist Charles Stanley Reinhart [ii] entitled “Let Us Have Peace.” Depicting the occasion of Red Cloud’s introduction to President Grant, the illustration—far more mythic than realistic—abounds with symbolism. Reinhart portrays Red Cloud bare-chested as a means of underscoring his “Herculean” physique—with rippled, well-developed musculature and powerful, sinewy arms. His fringed breechcloth, belt, and leggings are all elaborately beaded; in addition, his body is adorned with a plumed headdress and several distinctive pieces of jewelry—large, crescent-shaped earrings, a bracelet, and bear claw necklace. The chief’s appearance is rendered even more exotic by the three horizontal stripes painted just below his left eye; in the totality of these decorative details, the illustration presents, in Twain’s words, “a being to fall down and worship” (Collected Tales, Tales, Sketches, Speeches, & Essays, Vol. 1, p.442)—a literal incarnation of the quintessential “Noble Savage.”

“Let Us Have Peace.” Ulysses S. Grant and Jacob Cox, Secretary of the Interior, greeting Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, and Swift Bear during visit of Indian delegation with Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Ely S. Parker. Illustration by C.S. Reinhart. First appeared in Harper’s Weekly (June 18, 1870) p.385.

0 Comments