Editor’s Note: CMTS is committed to giving accurate, accessible information related to Mark Twain, his literature, his circle, and his world. These resource pages have been written by Mark Twain scholars, often times experts in the particular field. These are meant to be reliable, efficient resources for teachers, students, enthusiasts, and the general public.

If you are a scholar who is interested in creating and adding a Mark Twain Studies information page to our growing collection, please contact Director Joseph Lemak (jl****@****ra.edu).

About the Author

Lawrence Howe, Professor Emeritus of English in Film Studies at Roosevelt University, is a past editor of Studies in American Humor and author of Mark Twain and the Novel: The Double-Cross of Authority, and co-editor of Mark Twain and Money: Language, Capital, and Culture, and Refocusing Chaplin: A Screen Icon through a Critical Lens, as well as numerous articles on a wide range of topics in American studies. In 2014-15, he was the Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies in Denmark, and in 2020-2022 he was president of the Mark Twain Circle of America. He has enjoyed the generous support and recognition of the Center for Mark Twain Studies for more than a decade, including being honored with the Henry Nash Smith Award in 2022.

Professor Howe has participated in a number of CMTS events and given numerous lectures, including:

- Lawrence Howe, “Skewering Gilded Age Corruption: The Visual Satire of Thomas Nast” (October 12, 2024 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Lawrence Howe, “Mark Twain, Property, and Poetry” (May 31, 2023 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Lawrence Howe, “Scandal at Stormfield: Mark Twain’s ‘Ashcroft-Lyon Manuscript’” (June 3, 2020 – Online)

- Lawrence Howe, “Mark Twain and America’s Ownership Society” (October 17, 2012 – Quarry Farm Barn)

Life on the Mississippi

Samuel Clemens’s childhood in Hannibal and his career as a steamboat pilot in his early twenties established the importance of the Mississippi River to him during his formative years. Without those experiences, it’s a safe bet that we wouldn’t have Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In light of the river’s influence on Mark Twain, it’s somewhat surprising that Life on the Mississippi has been relatively overlooked. For years, when this travel book has received attention, a majority of critics discounted it as a disappointment. I argue that this assessment is short-sighted; it’s clear that Twain took this work very seriously, asserting in the book’s opening sentence, “The Mississippi is well worth reading about.” [i] This is not an idle claim; the river as a topic had long attracted his attention. His desire to write a Mississippi book gestated for almost two decades before it came to pass. In an 1866 letter to his mother, he alludes to a secret plan for a book of some 300 pages, the last third of which will have to be completed in St. Louis, which the editors of the Mark Twain Project note was a book about the Mississippi. [ii] In a letter to his wife Oliva five years later, he explicitly mentions his intention to write a “standard work” on the mighty river. [iii] He predicts that the project will include two months of traveling on the river, “and then look out!”—which comes close to what his 1882 Mississippi research trip entailed, about a decade after his letter to Olivia.

Life on the Mississippi (1887) first edition

Mark Twain’s Idiosyncratic Method

It was rare that Mark Twain wrote any of his longer works in one go. Usually, his composition was interrupted by periods of neglect, and in some cases these hiatuses were long. Life on the Mississippi falls into the latter category. As a result of its prolonged development, the book evolved into a project rather distinct from his other travel books. Indeed, the original composition of Life on the Mississippi did not involve a trip to the river; instead, it was a seven-part series of reminiscences of his days as a cub-pilot on Mississippi steamboats, which appeared in the Atlantic from January to August 1875 (with no installment published in the July issue). Yet even this successful magazine series came about nearly by accident. In 1874, Mark Twain made his debut in the Atlantic with “A True Story Repeated Word for Word as I Heard It.” William Dean Howells, editor of the magazine who would become Twain’s lifelong friend and literary sounding board, admired the vernacular authenticity and dramatic effect of Twain’s story of a formerly enslaved woman who recounts her reunion with her adult son who had been sold away from her as a young child. And Howells asked Twain if he had anything else for the Atlantic. Eager to capitalize on his first flush of success in the prestigious magazine, Twain mulled the offer over for several weeks only to admit to Howells that he would not be able to take advantage of the opportunity. On the same October afternoon when Twain sent his letter of demurral, he was on a routine walk with his friend and Hartford minister Joseph Twichell. Their conversation led to Twain recollecting his early career as a Mississippi steamboat pilot, to which Twichell exclaimed, according to Twain, “What a virgin subject to hurl into a magazine!” [iv] Suffused with confidence about the merits of this idea, Twain hurried home to write Howells, telling him to disregard his earlier letter and promising him that he would not only have an article for the Atlantic’s January 1875 issue, but an entire series. Convinced that he was uniquely equipped to provide vivid accounts of the romance of riverboat piloting, Twain promised Howells as many as nine installments; the seven that he produced would appear under the title “Old Times on the Mississippi.” The sketches were greeted warmly by readers of the magazine, as well as those of New York, St. Louis, and San Francisco periodicals where the series was pirated them. The success of “Old Times” provided Twain the confidence to return to the stalled manuscript of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which led directly into Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Still, Twain’s most celebrated novel also hit a snag about one-third of the way into the narrative. Pigeon-holing the manuscript for several years, Twain turned to other works, most notably Life on the Mississippi. After a research trip on the river in 1882, the year of a 100-year flood, Twain recommenced work on the book-length project in 1882-1883. He began by dividing the seven Atlantic sketches into chapters 4-17, framing these with three chapters before and three after, and then pivoting to 40 chapters of primarily contemporary observations that he had made during the 1882 return trip on the river. Like some of Twain’s other travel books, Part 2 is composed of seemingly random observations. The loose narrative of the trip documents the changes in the river and the life of its communities, as well as commentary on the river taken from other published sources. The text’s bifurcated structure of personal reminiscences from the antebellum period and the pastiche of observations from 1882 reflect the shift in literary tastes from the romanticism that prevailed prior to the Civil War and the realism that characterized the national ethos after it.

Mark Twain, circa 1880.

Critical Assessments

The humor, nostalgia, and personal voice of the “Old Times” sketches have led most critics to praise the first portion of the book and to judge the balance of the book as not only a disappointment but a failure. Prompted by the value accorded to organic unity by New Criticism of the early and mid-twentieth century, these assessments presumed that Twain’s intention in Life on the Mississippi was something quite different from what the text shows us that it is. For Life on the Mississippi is deliberately not unified, nor was the nation that inspired it. In other words, the critical assumption that the book’s two halves are at crossed purposes is predicated on the idea that Mark Twain had one purpose. The text, however, provides countervailing evidence.

Additionally, critics in this camp surmise that Twain was beholden to the requirements of the subscription publication, that his contract demanded a certain number of words to yield a book of substantial heft. This obligation, it has often been suggested, led him to import as many as 10,000 words copied from other sources, most of which appear in Part 2 of the volume. The allegation that Twain desperately imported seemingly random information from other sources simply to fulfill the word count of subscription publishing has been offered as evidence to support the claim that Twain made an already bad design decidedly worse. However, this charge ignores the fact that he had excluded more than 15,000 words of original composition from the final manuscript. If the length required by subscription publishing was the driving motivation, he had no need to introduce material from other sources. Clearly, though, he made a choice to exclude those 15,000 of his own words and to rely on information from others who had written about the river and its inhabitants at various points in the history of the North American continent. That compositional decision refutes the basis of this particular disparaging criticism. Something else is going on in the motley composition Life on the Mississippi than simply fulfilling a contract.

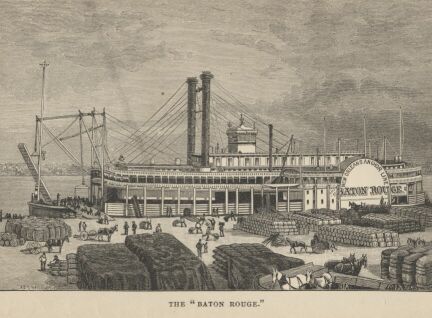

“The ‘Baton Rouge.'” Illustration from Life on the Mississippi (1883) Frontispiece.

Sam Clemens, Pilot; Mark Twain, Writer

Because Life on the Mississippi was written at two different times, corresponding to two different periods in Twain’s life, the divergent modes of the “Od Times” chapters and the travel account in the subsequent chapters register a shift in Twain’s professional identity. Although he was a writer when he composed “Old Times,” his focus in the sketches is on how he became a Mississippi steamboat pilot. That is, Part 1 of the book reflects his youthful aspiration and subsequent participation in the profession of steamboat piloting. His first fascination with steamboat life is inspired by the vitality he perceives in the vigorous, authoritative language of steamboatmen. Early on, he describes being in awe of the blustery orders of the steamboat’s mate, “discharged … like a blast of lightning, and sen[ding] a long, reverberating peal of profanity thundering after it.”[v] He provides a sample of such forceful speech and confides, “I wished I could talk like that.” [vi]

He soon recognizes that the real authority speech is that of the steamboat pilot, who commands from on high in the pilothouse and who answers to no one—a romantic figure if ever there was one. Seeking to join this august fraternity, he signs on as an apprentice to a celebrated pilot, Horace Bixby. Despite being 22-25 years old during this period, Twain portrays himself as a naïve adolescent, a far cry from the young man who had begun to enjoy a more cosmopolitan outlook while supporting himself for about seven years in the print shops of major cities like Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and New York. In his cub-pilot memoir, he depicts his apprenticeship as a series of humiliating trials from which he gradually develops expertise. But this achievement comes at a price. In a famous passage, Twain recounts how his piloting education had deprived him of his ertstwhile aesthetic appreciation of the riverscape:

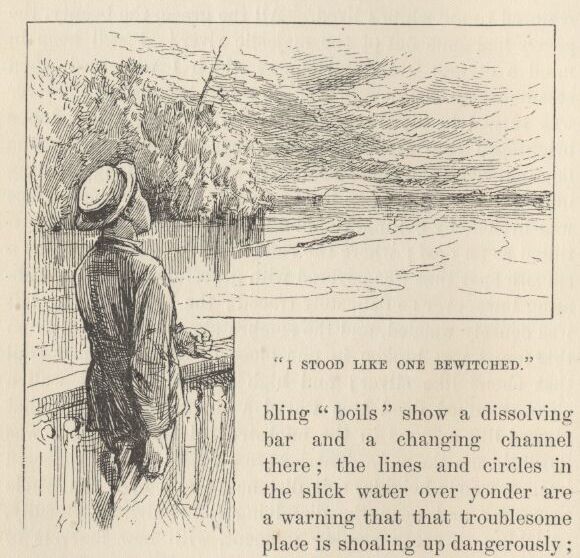

Now when I had mastered the language of this water and had come to know every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. I had lost something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry had gone out of the majestic river! I still keep in mind a certain wonderful sunset which I witnessed when steamboating was new to me. A broad expanse of the river was turned to blood; in the middle distance the red hue brightened into gold, through which a solitary log came floating, black and conspicuous; in one place a long, slanting mark lay sparkling upon the water; in another the surface was broken by boiling, tumbling rings, that were as many-tinted as an opal; where the ruddy flush was faintest, was a smooth spot that was covered with graceful circles and radiating lines, ever so delicately traced; the shore on our left was densely wooded, and the somber shadow that fell from this forest was broken in one place by a long, ruffled trail that shone like silver; and high above the forest wall a clean-stemmed dead tree waved a single leafy bough that glowed like a flame in the unobstructed splendor that was flowing from the sun. There were graceful curves, reflected images, woody heights, soft distances; and over the whole scene, far and near, the dissolving lights drifted steadily, enriching it, every passing moment, with new marvels of coloring. I stood like one bewitched.

–Life on the Mississippi (1883), chpt.9, p.119

“I Stood Like One Bewitched.” Illustration from Life on the Mississippi (1883), Chpt.9, p.120.

After describing how he had once marveled at a radiant Mississippi sunset, he admits that such a breathtaking spectacle no longer moves him: “No, the romance and the beauty were all gone from the river. All the value any feature of it had for me now as the amount of usefulness it could furnish toward compassing the safe piloting of a steamboat.” [vii]

If the pilot’s job prioritizes usefulness, enabling him to deliver his passengers and cargo expediently and without incident, the writer’s task is just the opposite. A vibrant narrative needs conflict, unexpected plot twists, vivid characters, and the indulgence of picturesque detail—the very elements that Sam Clemens’s steamboat experience had taught him to ignore. Twain subtly underscores this point in describing the experience of the citizens of Vicksburg who endured a six-week siege in 1863 by Union troops. Twain notes that the experience rendered the survivors incapable of telling their story with any vitality:

A week of their wonderful life there would have made their tongues eloquent forever perhaps; but they had six weeks of it, and that wore the novelty all out; they got used to being bomb-shelled out of home and into the ground; the matter became commonplace. After that, the possibility of their ever being startlingly interesting in their talks about it was gone.

–Life on the Mississippi (1883), chpt.XXXV, p.379

In contrast to the Vicksburghers, a man with only cursory knowledge of the Civil War whose imagination and storytelling talent would not silenced by overwhelming experience—a man much like himself.

Granted the “Old Times” sketches include plenty of the kinds of interesting elements that he claims to have forfeited as a pilot. But as his piloting career came to an end, he wound his way into a new one that granted him restored his narrative ability. He notes in Chapter XXI, “by and by the war came, commerce was suspended, my occupation was gone.”[viii] He then enumerates the variety of other livelihoods he has pursued: “silver miner in Nevada,” “newspaper reporter,” “gold miner in California,” “reporter in San Francisco,” “special correspondent in the Sandwich Islands, “roving correspondent in Europe and the East,” “instructional torch-bearer on the lecture platform,” and “finally a scribbler of books,” a professional trajectory that readers familiar with Innocents Abroad and Roughing It would have recognized. Two aspects of this personal account are noteworthy: first, the importance of Chapter 21 in encapsulating his career during the twenty-one years during which he has been absent from the Mississippi, which the correspondence of the chapter number and the duration of his absence subtly suggests; and second, the arc of his experience has resulted in him becoming a “scribbler of books.” In other words, he composes Part 2 of Life on the Mississippi not as a former pilot as in Part 1, but as a writer. And the focus of his attention in the travel narrative is not primarily recollection; it is observation about the changes, first, in steamboating and piloting, and, second—and in the country itself.

0 Comments