“From Independent Scholar to Scrub Angel: My Time at Quarry Farm” (A Quarry Farm Testimonial)

Eutsey has given a number of talks for CMTS, including:

- Dwayne Eutsey, “‘I have always preached’: Mark Twain and Liberal Religion” (October 29, 2025 – Quarry Farm Barn)

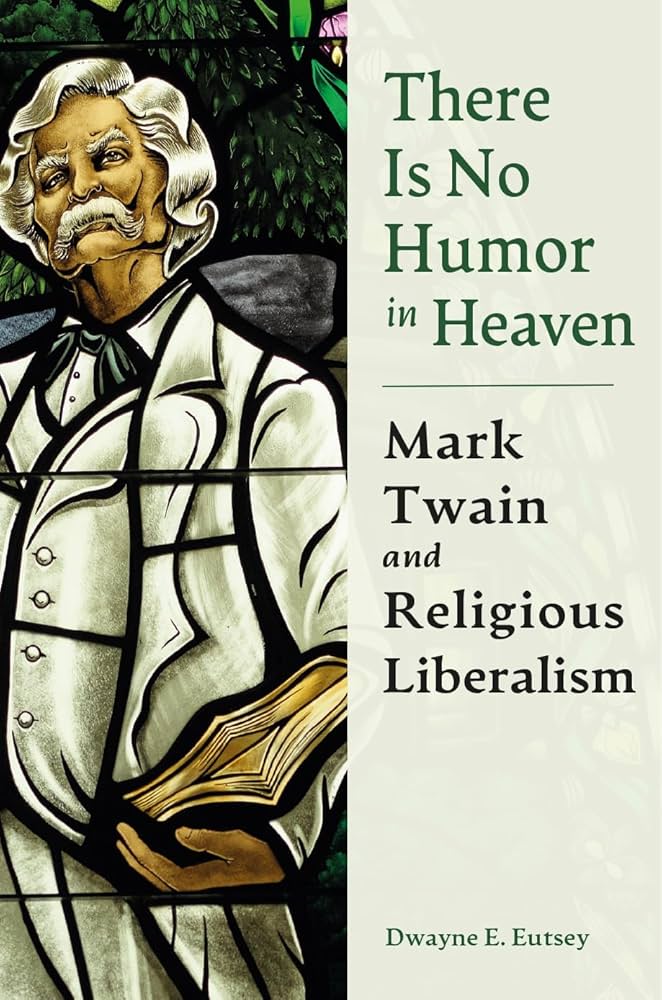

- Dwayne Eutsey, “There is no humor in heaven’: Mark Twain and Religious Liberalism” (October 5, 2022 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Dwayne Eutsey, “‘Never Be In A Hurry to Believe’: How Joe Twichell’s Visits to Elmira and Cornell May Have Saved Huck Finn’s Soul” (August 23, 2018 – Chemung Valley History Museum)

- Dwayne Eutsey, “‘Never Be In A Hurry to Believe’: How Joe Twichell’s Visits to Elmira and Cornell May Have Saved Huck Finn’s Soul” (August 23, 2018 – Chemung Valley History Museum)

As an independent scholar, my association with the Center for Mark Twain Studies (CMTS) has been crucial to writing my recently published book, “There is No Humor in Heaven”: Mark Twain and Religious Liberalism (University of Missouri Press, 2025).

I researched this topic, first developed as my thesis for the Masters in Liberal Studies program at Georgetown University, for over three decades. Having a full-time, non-academic job and living in a rural community on Maryland’s Eastern Shore were among the reasons why it took so long to finish. Throw in raising three children with my wife as I struggled to research my unconventional approach to Mark Twain and religion, and you can see why I related to Huck Finn’s exasperation when he mused at the end of his narrative, “If I’d a knowed what a trouble it was to make a book I wouldn’t a tackled it.”

Fortunately, CMTS and its Quarry Farm Fellowship Program significantly eased the trouble of tackling this project by introducing me to a welcoming and supportive community of Twain scholars. CMTS also offered opportunities to share my research in peer-reviewed journals, international Twain conferences, academic seminars, and the Trouble Begins lecture series. As if that were not enough, being a Quarry Farm Fellow offered a week-long stay in the house where Mark Twain summered with his family—and where he wrote a few of his classics in his famed octagonal study overlooking the Chemung Valley.

Evening view from the Quarry Farm Porch

During my first visit there, I discovered by happenstance one such gem that proved pivotal to my research when Mark Woodhouse, the archivist at the time, invited me to have lunch with him in the Campus Center Dining Hall. It was early in my research and I still felt insecure about my thesis that Twain—often assumed a hostile critic of religion—actually had a more positive theological outlook than is generally recognized, even during his final decade. As I hesitantly explained my research to Mark, he offhandedly asked if I would be interested in looking through the personal notes of John Tuckey that the late scholar’s widow had recently donated to the Archives.

Because Twain’s Mysterious Stranger documents are an essential part of my thesis, Mark’s invitation was like someone casually offering me a sip from the Holy Grail. In the early 1960s, Tuckey’s groundbreaking research revealed that the nihilistic Mysterious Stranger posthumously published in 1916—the one most cited as evidence of Twain’s resignation to despair late in life—was not Twain’s intended version at all. It was, as William Gibson called it, a “cut, cobbled-together partially falsified text” published by Twain’s literary executor Albert Bigelow Paine. Tuckey was instrumental in establishing the only draft Twain completed, No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger, as his authentic final novella.

So, of course, I eagerly accepted Mark’s invitation. For the rest of the afternoon I sifted through binders of Tuckey’s accumulated notes for an unfinished study rethinking Twain’s outlook and creative vitality at the end of his life. Poring over these papers, spanning from the 1960s to shortly before Tuckey’s death in the 1980s, I found that I was on the same path as Tuckey had been in challenging decades of scholarship characterizing Twain succumbing to hopelessness in his last decade. Tuckey noted in the mid-‘60s:

“Certainly Mark Twain was no more consistently hopeless in the later years than he was consistent about most other things. And he had his exuberances and enthusiasm right on through. Moreover the despair-laden portion of Tw(ain)’s later work have received a disproportionate emphasis at the expense of other continuing elements.”

Mark Woodhouse, Archivist for the Elmira College Mark Twain Archives, in 2009

By the late 1970s, Tuckey’s view had evolved, offering profound insight into his more optimistic interpretation of Twain’s “dark writings” during his final years:

“In such times of loss or danger, we are inclined to live more intensely; to have a vastly heightened awareness of the context of relationships and events in which we find ourselves. And thus out of these negative and stressful times there may be a new deeper sensing, a recentering as it were of our consciousness, a revitalized kind of link-up to all that we perceive ourself so fatefully connected with, so that time that is one of darkness, even of despair, may indeed lead on through to a new stage of enlightenment.”

I would go on to share these and other gems left behind by John Tuckey in my book. But on that long ago afternoon in the Archives this find also encouraged me to continue my long and sometimes lonely quest to write that book—an endeavor made much less forlorn through the assistance and encouragement that everyone at CMTS and the Twain community extended to a grateful independent scholar laboring largely in obscurity on Maryland’s rural Eastern Shore.

0 Comments