Editor’s Note: CMTS is committed to giving accurate, accessible information related to Mark Twain, his literature, his circle, and his world. These resource pages have been written by Mark Twain scholars, often times experts in the particular field. These are meant to be reliable, efficient resources for teachers, students, enthusiasts, and the general public.

If you are a scholar who is interested in creating and adding a Mark Twain Studies information page to our growing collection, please contact Director Joseph Lemak (jl****@****ra.edu).

About the Author

Susan K. Harris has served on the faculties of the University of Kansas, Penn State, and Queens College, CUNY. Her specialties are Mark Twain Studies and Studies of American Women Writers. Among her six monographs are Mark Twain’s Escape from Time: A Study of Patterns and Images (U Missouri P, 1982); The Courtship of Olivia Langdon and Mark Twain (Cambridge, 1996); and God’s Arbiters: Americans and the Philippines, 1898-1902 (Oxford, 2011). She has edited three American women’s novels for Penguin/Putnam Press, the Library of America’s volume of Twain’s historical romances, and a Houghton Mifflin pedagogical edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Her most recent work is Mark Twain, The World, and Me (U Alabama P, 2020). Retired, she lives and writes in Brooklyn, NY.

Professor Harris has participated in a number of CMTS events and given numerous lectures, including:

- Susan K. Harris, Interview about her book Mark Twain, The World, and Me (October 21, 2020)

- Susan K. Harris, “Searching For The Ornithorhynchus: Mark Twain and Animal Conservation” (October 7, 2015 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Susan K. Harris, “Mark Twain and the Philippine-American War: “Hogwash” and “Pious Hypocrisy” (May 30, 2012 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Susan K. Harris, “Love Texts: The Role of Books in the Courtship of Olivia Langdon and Mark Twain” (November 13, 1996 – Quarry Farm)

- Susan K. Harris, “Olivia Langdon Clemens’s Reading” (April 29, 1992 – Quarry Farm)

- Susan K. Harris, “Overcoming Sin: The Audiences for Mark Twain’s ‘Hadleyburg’” (July 23, 1990 – Quarry Farm)

- Susan K. Harris, “Four Ways to Kill a Mackerel: Mark Twain and Laura Hawkins” (November 3, 1988 – Quarry Farm)

Photograph (from left to right) of Samuel Moffett, Olivia Clemens, Clara Clemens, Samuel Clemens, unidentified guest,

Martha Pond, and Officer aboard the U.S.S. Mohican, near Tacoma, Washington. August, 13, 1897.

Mark Twain did not write Following the Equator in a happy mood. The round-the-world lecture tour that preceded it, and the year of writing the book entailed, were fraught with personal and financial calamities. Accompanied by his wife, Oliva, and middle daughter Clara, Twain, then age 60, undertook the tour only because he had been forced to declare bankruptcy after the failure of both his publishing house, Charles L. Webster and Company, and the Paige typesetting machine which he had been bankrolling. The 13-month journey itself was grueling: beginning with trial lectures in Cleveland, Ohio, during an 1895 summer heat wave, and continuing to lecture on a West/Northwest trajectory up through the western U.S. and Canada until they reached Vancouver; then travelling by boat to, and by rail within, Australia, New Zealand, Ceylon, India, Mauritius, and South Africa—all then subjects of the British Empire–and ending in England in the summer of 1896. The lecture schedule left little down time, one consequence of which was that the aging Twain suffered from multiple bouts of painful carbuncles and nasty colds, forcing him to cancel performances and radically reducing his profits. Once settled in England, he, Olivia, and Clara awaited the arrival of their other two daughters, Susy and Jean, only to receive news that Susy was gravely ill. Clara and Olivia rushed home to nurse her, but by the time their steamboat reached New York, she was dead.

Following the Equator, then, was written over what was probably the worst year of Samuel Clemens’s life, his personal grief over Susy’s death compounded by his financial worries and his concern over the toll losing Susy was taking on Olivia’s health. And yet the book often transcends its author’s personal anguish. Like The Innocents Abroad, it is best read as a document illustrating the worldview of white Americans and Britons—Twain’s target readership—of the late 19th-century, a worldview that will make many of today’s readers uncomfortable. At the same time—and often intertwined with the racism and religious prejudices reflecting that worldview—there are passages and chapters that are expertly and brilliantly written, flashes of insight that eclipse prejudice, and turns of phrase that mark Twain’s inimitable humor. It’s a book that needs to be read within its historical contexts, but it is also a Mark Twain travelogue, full of sharp observations and humorous moments.

A word about editions. Like most of Mark Twain’s books, Following the Equator (1897) was published in both British and American editions, and although the majority of the content is the same between them, there are marked differences in the books’ formatting. The most striking difference is that the British edition (also 1897), titled More Tramps Abroad and published by Chatto and Windus, featured only 4 illustrations, whereas the American edition, published by the American Publishing Company, featured 193, by 11 different illustrators and photographers. Additionally, contents are distributed differently across the chapters, with paragraphs and sections appearing in different chapters depending on which edition one examines. The paragraphs themselves also tend to be longer in the British edition, at times encompassing sentences that are distributed across two or three far shorter paragraphs in the American edition. Reading the two editions side-by-side suggests that Chatto and Windus felt they could depend on a readership able to read sustained paragraphs, whereas the American Publishing Company understood their readers to need short paragraphs and many visual aids.

Formatting and illustrations aside, both editions conform to the protocols of travel literature, a popular 19th-century genre. As Jeffrey Melton notes in his essay on The Innocents Abroad, also featured on this CMTS website, “Travel literature is a varied and overlapping genre that combines the characteristics of journalism, autobiography, fiction, history, anthropology, and political analysis among others into a smorgasbord of narrative interpretation. As a composite literary form, it resists neat categorization.” Innocents was Twain’s first published travelogue; Following is his fifth, and last. During the interval between them he had worked out his formula, basing the first-person narrative on observations recorded in his notes, journals, and letters to friends; interspersed with newspaper articles about ongoing events; segments of other writers’ accounts of journeys; local histories, and ethnographic materials—all liberally sprinkled with illustrations, at least in the American edition. If Following was a purely visual project, it would be a collage, an assemblage of original drawings, newspaper clippings, photographs, and landscape paintings, interspersed with first-person narrative observations, opinions, analyses, and reminiscences. Little among existing documents, styles, and genres is off Twain’s table.

One of the challenges for writers of travel literature is striking a balance between readers’ comfort levels and their desire to learn about people, places, and cultures very different from their own. For the writer, this often entails catering to widely-held readers’ preconceptions—call them prejudices—while also giving as accurate information as the writers can access about “foreign” communities’ physiognomies, dress, domestic arrangements, arts, religions, and overall levels of “civilization.” The success of The Innocents Abroad lay in Twain’s skillful balancing of these factors. As Mellon notes, though, in that first travelogue, published in 1869, Twain did not question the moral aspects of his expert manipulation of western stereotypes. Following the Equator, I suggest, does.

Cover of More Tramps Abroad (1897)

first edition.

Cover of Following The Equator (1897)

first edition.

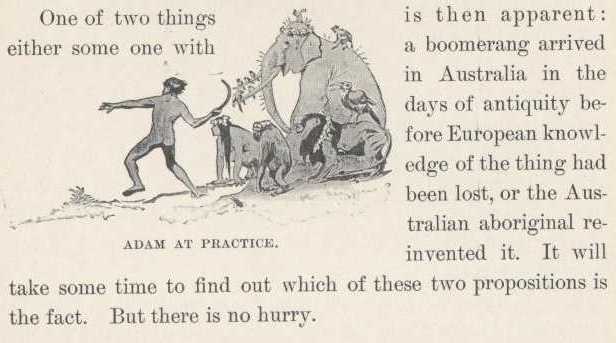

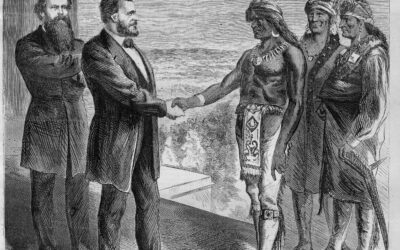

Twain’s uneasiness with his material manifests especially in his frequent switches of viewpoint. His treatment of Australian Aboriginals is a case in point. Though he never, to his knowledge, met an Australian Aborigine (by 1895 most coastal communities had retreated inland, though cities also contained communities of mixed race people), he became intensely interested in what he could learn of their arts and technologies, introducing the topic through an elderly settler who opines that it is a “great pity that the race had died out,” and noting that his informant “instanced [Aboriginal] invention of [weapons known as] the boomerang and the ‘weet-weet’ as evidences of their brightness; and … said he had never seen a white man who had cleverness enough to learn to do the miracles with those two toys that the aboriginals had achieved” (194) [i]. These “toys” caught Twain’s imagination, and he elaborates on their implementation in another chapter, taking his materials from interviews with and written records from whites who had observed their uses.

“Adam at Practice.” Illustration from

Following The Equator (1897) Chpt. XIX, p.194

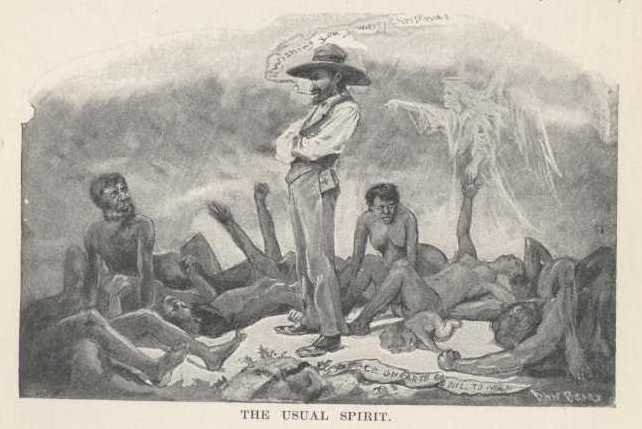

In passages like this, Twain appeals to white westerners, and especially Americans’, assumption that other races and cultures are inferior because they lack energy and ambition. But Twain is also on the verge of deeper insights in these chapters, ones that the constraints of the genre, and his need to sell copies, prevented him from elaborating but that come through in terse, ironic sentences interspersed with his accounts. After a brief (and coded) allusion to Aboriginal birth control methods, for instance, he notes that the need to control births ceased “after the white man came. The white man knew ways of keeping down the population which were worth several of [the Aboriginal’s]. The white man knew ways of reducing a native population 80 per cent, in 20 years. The native had never seen anything as fine as this” (208). Shortly after, Twain recounts—again from white sources, oral and written—stories about white settlers’ genocidal acts, including mass poisonings, in their drive to exterminate the native population.

“The Usual Spirit.” Illustration from Following The Equator. Chpt.XXI, p.211.

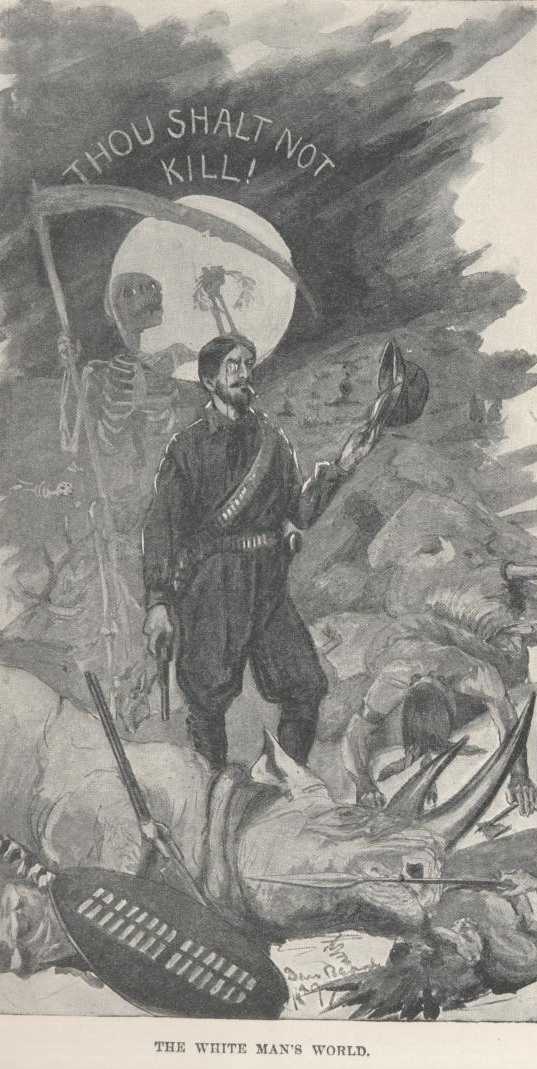

“The White Man’s World.” Illustration from Following The Equator. Chpt. XIX, p.187.

…..Continuing reading Professor Harris’s Following the Equator Information Page HERE.

0 Comments