“The Noble Red Man”

Published in the September 1870 issue of Galaxy magazine, “The Noble Red Man” is without question, the harshest depiction of Indians Mark Twain produced over the course of his long career. The circumstances that prompted the sketch’s composition, however, along with the author’s reasons for choosing to publish it in a New York literary periodical, have long been misunderstood. On first glance, the venom that permeates the piece is perplexing. It was written neither during a time of war nor in the immediate aftermath of a horrific massacre that inflamed popular anti-Indian sentiment, such as the Santee Sioux Uprising of 1862; indeed, Twain’s invective runs counter to the assimilationist goals of the peace policy spearheaded by President Ulysses S. Grant. The sketch is nonetheless a highly topical piece, a vitriolic response to a very different kind of event—the Eastern media’s effusive coverage of the June 1870 visit of two separate Sioux delegations—one led by the Brulé chief Spotted Tail, the other by Oglala leader Red Cloud—to Washington, DC to discuss the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty, signed two years earlier.

Contemporary newspaper reports of the Lakota leaders’ historic visit in the Washington Star, Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, and New York Times (as well as the New York Herald, Standard, and Evening Post) depict the Indians in lofty, idealized terms. Article after article emphasizes their imposing physical appearance and striking manner of dress, their “natural” eloquence, and innate dignity—in other words, the very same traits that constitute the basis of Twain’s attack in “The Noble Red Man.” While skeptics might dismiss this similarity as a coincidence, the writer’s personal reading habits, abiding interest in current events, and professional responsibilities as editor and co-owner of the Buffalo Express virtually assure his awareness of the sentimental rhetoric used in describing Red Cloud and Spotted Tail. Moreover, it is likely that this imagery—rather than the iconic fictional figures of Uncas and Chingachgook in James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans—represents the underlying inspiration for the sketch. According to Alan Gribben’s reconstruction of Twain’s library, he regularly read a number of New York dailies over the course of his career; in addition to the Times, Clemens claimed in 1888 that the Evening Post was his “favorite paper,” and stated in 1895 that he “couldn’t do without” the New York Herald. [i] But even if the extensive reports of the Lakotas’ Eastern sojourn somehow eluded him in these various metropolitan publications, the Buffalo Express reprinted—via telegraph—articles on this topic from both the Times and Tribune throughout the month of June.

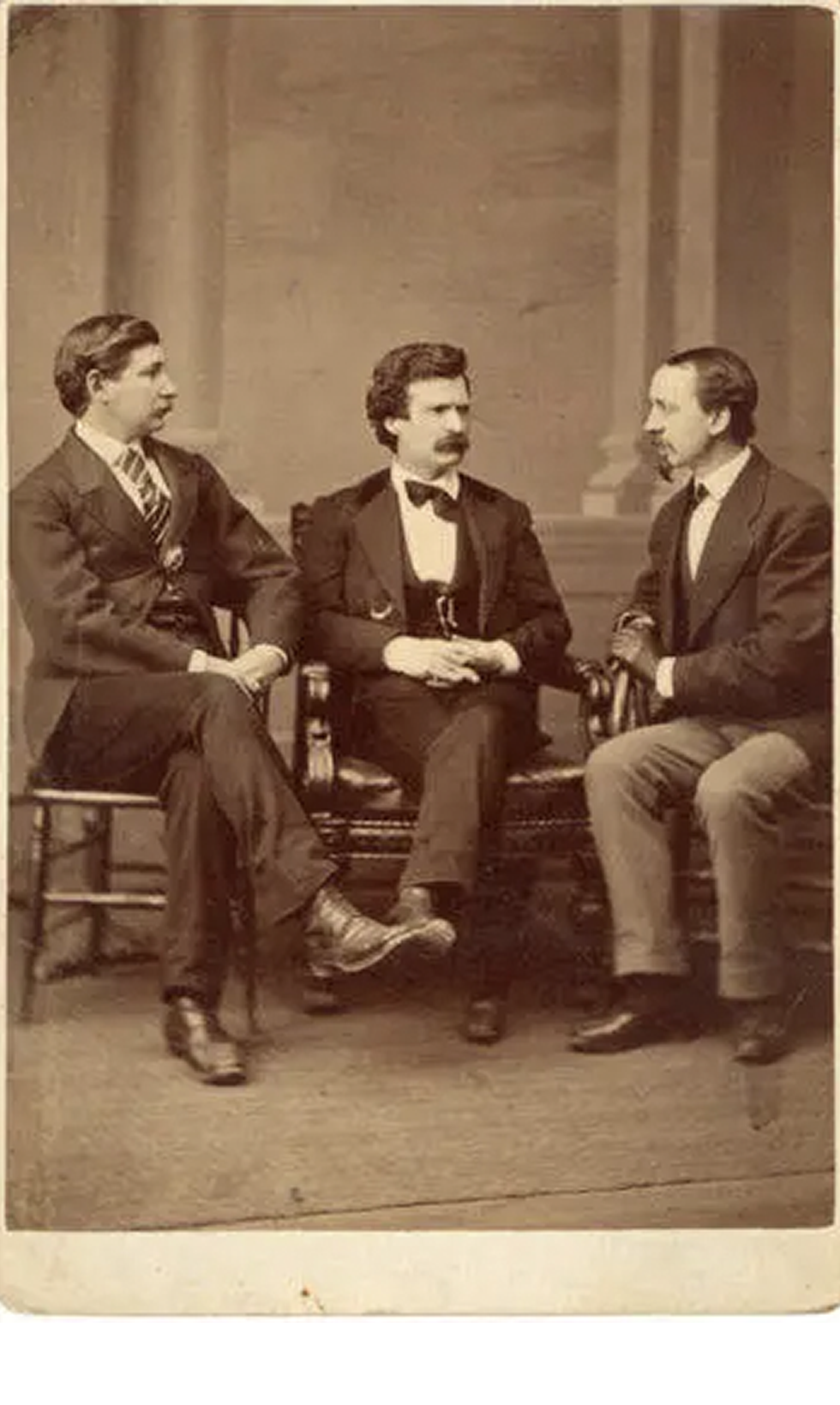

Photo taken in 1871 on a lobbying trip to Washington D.C. George Alfred Townsend, journalist (left); Mark Twain (center); David Gray, editor of the Buffalo Courier (right).

Because Red Cloud steadfastly refused to be photographed throughout his 1870 visit to Washington, print journalism—the daily accounts of his appearance and demeanor published in the New York Times and New York Tribune, among others—offers the only documentation of his stay. These articles were then used by artists to create the highly-romanticized images published in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in late June and early July. On June 18th, for example, the day after Red Cloud’s delegation boarded a west-bound train in New York City for their long trek home, Harper’s Weekly featured an iconic engraving by staff artist Charles Stanley Reinhart [ii] entitled “Let Us Have Peace.” Depicting the occasion of Red Cloud’s introduction to President Grant, the illustration—far more mythic than realistic—abounds with symbolism. Reinhart portrays Red Cloud bare-chested as a means of underscoring his “Herculean” physique—with rippled, well-developed musculature and powerful, sinewy arms. His fringed breechcloth, belt, and leggings are all elaborately beaded; in addition, his body is adorned with a plumed headdress and several distinctive pieces of jewelry—large, crescent-shaped earrings, a bracelet, and bear claw necklace. The chief’s appearance is rendered even more exotic by the three horizontal stripes painted just below his left eye; in the totality of these decorative details, the illustration presents, in Twain’s words, “a being to fall down and worship” (Collected Tales, Tales, Sketches, Speeches, & Essays, Vol. 1, p.442)—a literal incarnation of the quintessential “Noble Savage.”

“Let Us Have Peace.” Ulysses S. Grant and Jacob Cox, Secretary of the Interior, greeting Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, and Swift Bear during visit of Indian delegation with Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Ely S. Parker. Illustration by C.S. Reinhart. First appeared in Harper’s Weekly (June 18, 1870) p.385.

The size and prominence of this engraving, which appeared on the front page of one of America’s most popular periodicals, reinforced a sentimental stereotype that Mark Twain regarded as both inaccurate and dangerous. In “The Noble Red Man,” he offers a corrective counter-image of the Indian’s “natural self,” as he appears “out on the plains and in the mountains, not being on dress parade…[or] gotten up to see company”: “He is little, and scrawny, and black, and dirty; and judged by even the most charitable of our canons of human excellence, is thoroughly pitiful and contemptible. There is nothing in his eye or his nose that is attractive…He wears no feathers in his hair, and no ornament or covering on his head…He has no pendants in his ears…He wears no bracelets on his arms or ankles …He is not rich enough to possess a belt; he never owned a moccasin or wore a shoe in his life” (CTSS&E1, 443). While this cynical litany of denunciation (no feathers, no ornaments, no pendants, no bracelets) may be interpreted as a generic rejection of the “Noble Savage” stereotype, Reinhart’s illustration, in conjunction with the Times article that inspired it, suggests that Twain’s derisive allusion to the Indian’s diminutive, “scrawny” stature may in fact represent a reaction to the media’s depiction of Red Cloud.

Throughout the sketch, Twain underscores the legitimacy of his viewpoint by insisting that he—or more accurately, his narrative persona—speaks as a Westerner, someone whose firsthand observation of Native peoples affords privileged access into the alleged “truth” of their character. Thus, after describing the absurd, degraded appearance of a warrior bedecked in a “necklace of battered sardine-boxes and oyster-cans,” wearing a “weather-beaten stove-pipe hat” and old hoop skirt,” he adds a footnote explaining: “This is not a fancy picture; I have seen it many a time in Nevada, just as it is here limned” (CTSS&E1, 444). In Getting to be Mark Twain, Jeffrey Steinbrink characterizes the perspective of “The Noble Red Man” as a “manly, vaguely Western” counterpoint to the “effeminate softness” Twain identified with the “effete East Coast” (Steinbrink, 126). While the speaker’s regional affiliation is indisputable, the ethnocentrism of his views is by no means generically Western. [iii] The harsh, exaggerated quality of Twain’s language, particularly his use of sweeping racial generalizations—“All history and honest observation will show that the Red Man is a skulking coward and a windy braggart…[whose] heart is a cesspool of falsehood, of treachery, and of low and devilish instincts” (CTSS&E1, 444) suggest that these are the views of a defiant, hardline frontiersman, resolute in his conviction that the Indian is “nothing but a poor, filthy naked scurvy vagabond whom to exterminate were a charity to the Creator’s worthier insects and reptiles whom he oppresses.” The speaker reiterates this view later in the same paragraph, declaring the Indian “a good, fair, desirable subject for extermination if ever there was one” (CTSS&E1, 445).

By incorporating verifiable biographical detail and allusions to personal observation into the sketch, he blurs the already nebulous boundary between Sam Clemens and Mark Twain, and simultaneously fleshes out the dimensions of his nom de plume by adding a sobering new trait—rabid Indian-hater—to his reputation as the “wild humorist of the Pacific Slope.” In his 2003 study, Mark Twain and the American West, Joseph Coulombe characterizes “The Noble Red Man” as the writer’s attempt to “distance his persona from potentially negative elements of the West [in order] to gain a greater readership in the East” (Coulombe, 106). Considering both the time and place of its publication, however, the text is in fact a calculated declaration of difference—a bold, finger-wagging reproach directed at those living along “the Atlantic seaboard” who “wail” in misguided “humanitarian sympathy” over the plight of the “poor abused Indian” (CTSS&E1, 446). Such a gambit—even embedded within the broader framework of a monthly humor column—was far more likely to alienate liberal Galaxy readers than curry favor with them. Like the “Whittier Birthday Speech” delivered in Boston seven years later, “The Noble Red Man” is a veiled act of aggression, an occasion upon which Twain—adopting the guise of a brash frontiersman—defines himself in opposition to his genteel Eastern audience.

Mark Twain concludes the sketch by citing horrific statistics which he claims are found in “Dr. Keim’s excellent book”—Sheridan’s Troopers on the Borders (1870)—although they do not in fact appear in its pages. He italicizes these atrocities for further emphasis:

From June 1868, to October, 1869, the Indians massacred nearly 200 white persons and ravished over forty women captured in peaceful outlying settlements along the border, or belonging to emigrant trains traversing the settled routes of travel. Children were burned alive in the presence of their parents. Wives were ravished before their husbands’ eyes. Husbands were mutilated, tortured, and scalped, and their wives compelled to look on. (CTSS&E1, 445–46)

These “facts and figures,” he insists, “are official, and they exhibit the misunderstood Son of the Forest in his true character—as a creature devoid of brave or generous qualities, but cruel, treacherous, and brutal.” While appalling interracial violence was indeed commonplace in the West during the second half of the 19th century, Twain’s description is notable both for its lack of historical context and the idealized image it presents of prototypical Anglo-American families living “in peaceful outlying settlements” or traversing “settled routes of travel.” They are thus portrayed as blameless victims rather than colonial aggressors who systematically dispossessed indigenous tribes of their ancestral homelands.

Although Mark Twain’s intention in “The Noble Red Man” may have been to counter the romantic representation of Indians both in the eastern press and the work of writers such as James Fenimore Cooper and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, its caustic hyperbole substitutes one reductive racial stereotype for another through repeated insistence that Indians are “ignoble—base and treacherous, and hateful in every way” (CTSS&E1, 444). As Jeff Steinbrink has aptly observed, while the sketch “gets underway as an exercise in deflating sentimental excess or distortion…the rest is given over to invective, derogation, and manifest racism. Its intensely personal vituperation carries [the writer] far beyond the attitude of edgy candor needed to correct romantic misrepresentations” (125).

[i] Alan Gribben, Mark Twain’s Literary Resources, 530. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2022.

[ii] American painter and illustrator Charles Stanley Reinhart (1844-1896) was born in Pittsburgh, but received his artistic training in Paris and Munich. In addition to illustrating books by Charles Dudley Warner, Sarah Orne Jewett, and Willa Cather, he contributed engravings to many leading 19th century periodicals, publishing over two hundred images in Harper’s Weekly alone. Some of his Harper’s illustrations are signed, “From a Sketch by C.S. Reinhart,” indicating that he was employed as one of the magazine’s “special artists”—an individual who traveled to various field locations and made on-the-spot drawings of newsworthy events which were then transported to New York “where a group of engravers was deployed to copy them onto wooden blocks” (Coward 127). Other images, however, such as the 1870 engravings of Red Cloud, simply bear the initials C.S.R. and the vague notation “Drawn by C.S. Reinhart” following the title in the caption printed below the illustration, suggesting that they were produced at a physical distance from the scene depicted, in all likelihood at Harper’s Manhattan studio. As historian John Coward has observed, these studio engravings tended to be both impressionistic and “quite imaginary, created solely from written reports” (127). As such,

the accuracy of [most Indian] illustrations in Leslie’s and Harper’s was problematic. At their best, such images might capture some sense of reality, at least from the (white) artist’s point of view. But the illustrated papers did not want images of the mundane or dull. Artists and engravers had every incentive to improve reality, to make their images as interesting and exciting as possible. Such images might depart from the literal truth, but they could be justified as emotionally true (128).

[iii] Utah representative William Henry Hooper, for example, addressed Congress in early June of 1870, arguing that if indigenous peoples were treated justly, there would be no Indian wars. He stated: “The Mormons have sent more than eighty thousand persons, with their property, through the Indian country, across the plains, in the last twenty-two years, and have never lost a life, an animal, or a bale of goods by Indian depredation” (quoted in the New York Evening Post, 13 June 1870).

Works Cited and Suggested Further Readings

Budd, Louis J., ed. Mark Twain: Collected Tales, Sketches, Speeches & Essays, 1852–1890. New York: The Library of America, 1992.

Coulombe, Joseph. Mark Twain and the American West. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003.

Coward, John. The Newspaper Indian: Native American Identity in the Press, 1820–1890. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Driscoll, Kerry. Mark Twain among the Indians and Other Indigenous Peoples. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018.

Gribben, Alan. Mark Twain’s Literary Resources: A Reconstruction of His Library and Reading. Vol. 2. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2022.

Steinbrink, Jeffrey. Getting to Be Mark Twain. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

About the Author

Kerry Driscoll, Professor of English Emerita at the University of Saint Joseph (West Hartford, CT) is currently Associate Editor at the Mark Twain Papers and Project at the University of California, Berkeley. A long-time Twain scholar, she is the author of Mark Twain among the Indians and Other Indigenous Peoples (University of California Press, 2018), the first book-length study of the writer’s evolving views regarding the aboriginal inhabitants of North America and Australasia, and his deeply conflicted representations of them in fiction, newspaper sketches, and speeches. She is past president of the Mark Twain Circle of America as well as a contributing editor to its journal, the Mark Twain Annual. She served on the Mark Twain House and Museum’s Board of Trustees from 2017-23, and is currently a member of their honorary Advisory Council. In 2022, she received the Louis J. Budd award for distinguished scholarship from the Mark Twain Circle of America in recognition of her groundbreaking research.

Professor Driscoll has participated in a number of CMTS events and given numerous lectures, including:

- Kerry Driscoll, Ann Ryan, and Matt Seybold, “Beyond the White Suit: Mark Twain in the Twenty-First Century” (October 16, 2025 – Quarry Farm First Floor Library)

- Kerry Driscoll, “A Delicate Balance: Work and Play in Mark Twain’s Creative Process” (October 15, 2025 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Kerry Driscoll, “‘Talking is the thing’: Mark Twain’s Bold Experiment in Empowering Women’s Voices” (August 4, 2022 – Elmira College Campus)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain’s Masculinist Fantasy of The West” (October 2, 2021 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain and the American Indian” (July 11, 2018 – The Park Church)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain, The Maori, and The Mystery of Livy’s Jade Pendant” (October 1, 2014 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Kerry Driscoll, “‘Eating Indians for Breakfast’: Racial Ambivalence and American Identity in The Innocents Abroad” (October 21, 1998 – Quarry Farm)

- Kerry Driscoll, “A Tramp Abroad: Mark Twain in Heidelberg” (March 28, 1990 – Quarry Farm)

- Kerry Driscoll, “Mark Twain and the American Indian” (1986 – Quarry Farm Barn)