Following The Equator

Photograph (from left to right) of Samuel Moffett, Olivia Clemens, Clara Clemens, Samuel Clemens, unidentified guest,

Martha Pond, and Officer aboard the U.S.S. Mohican, near Tacoma, Washington. August, 13, 1897.

Mark Twain did not write Following the Equator in a happy mood. The round-the-world lecture tour that preceded it, and the year of writing the book entailed, were fraught with personal and financial calamities. Accompanied by his wife, Oliva, and middle daughter Clara, Twain, then age 60, undertook the tour only because he had been forced to declare bankruptcy after the failure of both his publishing house, Charles L. Webster and Company, and the Paige typesetting machine which he had been bankrolling. The 13-month journey itself was grueling: beginning with trial lectures in Cleveland, Ohio, during an 1895 summer heat wave, and continuing to lecture on a West/Northwest trajectory up through the western U.S. and Canada until they reached Vancouver; then travelling by boat to, and by rail within, Australia, New Zealand, Ceylon, India, Mauritius, and South Africa—all then subjects of the British Empire–and ending in England in the summer of 1896. The lecture schedule left little down time, one consequence of which was that the aging Twain suffered from multiple bouts of painful carbuncles and nasty colds, forcing him to cancel performances and radically reducing his profits. Once settled in England, he, Olivia, and Clara awaited the arrival of their other two daughters, Susy and Jean, only to receive news that Susy was gravely ill. Clara and Olivia rushed home to nurse her, but by the time their steamboat reached New York, she was dead.

Following the Equator, then, was written over what was probably the worst year of Samuel Clemens’s life, his personal grief over Susy’s death compounded by his financial worries and his concern over the toll losing Susy was taking on Olivia’s health. And yet the book often transcends its author’s personal anguish. Like The Innocents Abroad, it is best read as a document illustrating the worldview of white Americans and Britons—Twain’s target readership—of the late 19th-century, a worldview that will make many of today’s readers uncomfortable. At the same time—and often intertwined with the racism and religious prejudices reflecting that worldview—there are passages and chapters that are expertly and brilliantly written, flashes of insight that eclipse prejudice, and turns of phrase that mark Twain’s inimitable humor. It’s a book that needs to be read within its historical contexts, but it is also a Mark Twain travelogue, full of sharp observations and humorous moments.

A word about editions. Like most of Mark Twain’s books, Following the Equator (1897) was published in both British and American editions, and although the majority of the content is the same between them, there are marked differences in the books’ formatting. The most striking difference is that the British edition (also 1897), titled More Tramps Abroad and published by Chatto and Windus, featured only 4 illustrations, whereas the American edition, published by the American Publishing Company, featured 193, by 11 different illustrators and photographers. Additionally, contents are distributed differently across the chapters, with paragraphs and sections appearing in different chapters depending on which edition one examines. The paragraphs themselves also tend to be longer in the British edition, at times encompassing sentences that are distributed across two or three far shorter paragraphs in the American edition. Reading the two editions side-by-side suggests that Chatto and Windus felt they could depend on a readership able to read sustained paragraphs, whereas the American Publishing Company understood their readers to need short paragraphs and many visual aids.

Formatting and illustrations aside, both editions conform to the protocols of travel literature, a popular 19th-century genre. As Jeffrey Melton notes in his essay on The Innocents Abroad, also featured on this CMTS website, “Travel literature is a varied and overlapping genre that combines the characteristics of journalism, autobiography, fiction, history, anthropology, and political analysis among others into a smorgasbord of narrative interpretation. As a composite literary form, it resists neat categorization.” Innocents was Twain’s first published travelogue; Following is his fifth, and last. During the interval between them he had worked out his formula, basing the first-person narrative on observations recorded in his notes, journals, and letters to friends; interspersed with newspaper articles about ongoing events; segments of other writers’ accounts of journeys; local histories, and ethnographic materials—all liberally sprinkled with illustrations, at least in the American edition. If Following was a purely visual project, it would be a collage, an assemblage of original drawings, newspaper clippings, photographs, and landscape paintings, interspersed with first-person narrative observations, opinions, analyses, and reminiscences. Little among existing documents, styles, and genres is off Twain’s table.

One of the challenges for writers of travel literature is striking a balance between readers’ comfort levels and their desire to learn about people, places, and cultures very different from their own. For the writer, this often entails catering to widely-held readers’ preconceptions—call them prejudices—while also giving as accurate information as the writers can access about “foreign” communities’ physiognomies, dress, domestic arrangements, arts, religions, and overall levels of “civilization.” The success of The Innocents Abroad lay in Twain’s skillful balancing of these factors. As Mellon notes, though, in that first travelogue, published in 1869, Twain did not question the moral aspects of his expert manipulation of western stereotypes. Following the Equator, I suggest, does.

Cover of More Tramps Abroad (1897)

first edition.

Cover of Following The Equator (1897)

first edition.

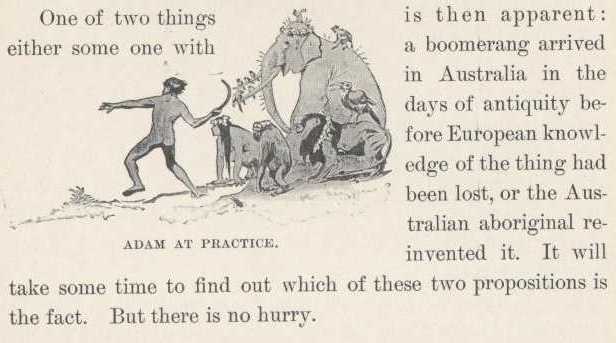

Twain’s uneasiness with his material manifests especially in his frequent switches of viewpoint. His treatment of Australian Aboriginals is a case in point. Though he never, to his knowledge, met an Australian Aborigine (by 1895 most coastal communities had retreated inland, though cities also contained communities of mixed race people), he became intensely interested in what he could learn of their arts and technologies, introducing the topic through an elderly settler who opines that it is a “great pity that the race had died out,” and noting that his informant “instanced [Aboriginal] invention of [weapons known as] the boomerang and the ‘weet-weet’ as evidences of their brightness; and … said he had never seen a white man who had cleverness enough to learn to do the miracles with those two toys that the aboriginals had achieved” (194) [i]. These “toys” caught Twain’s imagination, and he elaborates on their implementation in another chapter, taking his materials from interviews with and written records from whites who had observed their uses.

“Adam at Practice.” Illustration from

Following The Equator (1897) Chpt. XIX, p.194

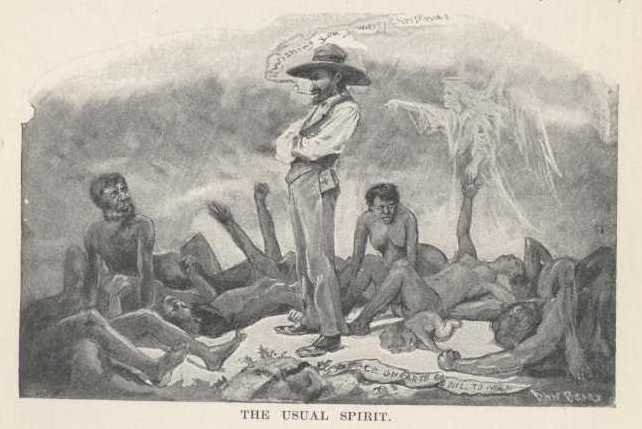

Twain also uses secondary sources, primarily from a memoir by Mrs. Campbell Praed, to teach his readers a bit about the fierce, and bloody, history of white settler/Aboriginal conflict over the land and its uses. Yet as he details this history, on the Australian mainland and in Tasmania [i], using published histories, memoirs, newspaper articles, and other documents, we can see how, in this last travelogue, the formats and protocols of travel literature are breaking down for Twain. Never one to hone his writings for consistency, in Following the Equator Twain’s inconsistencies appear from chapter to chapter, sometimes paragraph by paragraph. At times, he appeals to his white readers prejudices, for instance following up his admiration for Aboriginal intelligence by referring to them as “savages” and concluding that “they were lazy—always lazy,” because they had not invented housing, agriculture, or the other material arts that, for Westerners, signaled “civilization.”

In passages like this, Twain appeals to white westerners, and especially Americans’, assumption that other races and cultures are inferior because they lack energy and ambition. But Twain is also on the verge of deeper insights in these chapters, ones that the constraints of the genre, and his need to sell copies, prevented him from elaborating but that come through in terse, ironic sentences interspersed with his accounts. After a brief (and coded) allusion to Aboriginal birth control methods, for instance, he notes that the need to control births ceased “after the white man came. The white man knew ways of keeping down the population which were worth several of [the Aboriginal’s]. The white man knew ways of reducing a native population 80 per cent, in 20 years. The native had never seen anything as fine as this” (208). Shortly after, Twain recounts—again from white sources, oral and written—stories about white settlers’ genocidal acts, including mass poisonings, in their drive to exterminate the native population.

“The Usual Spirit.” Illustration from Following The Equator. Chpt.XXI, p.211.

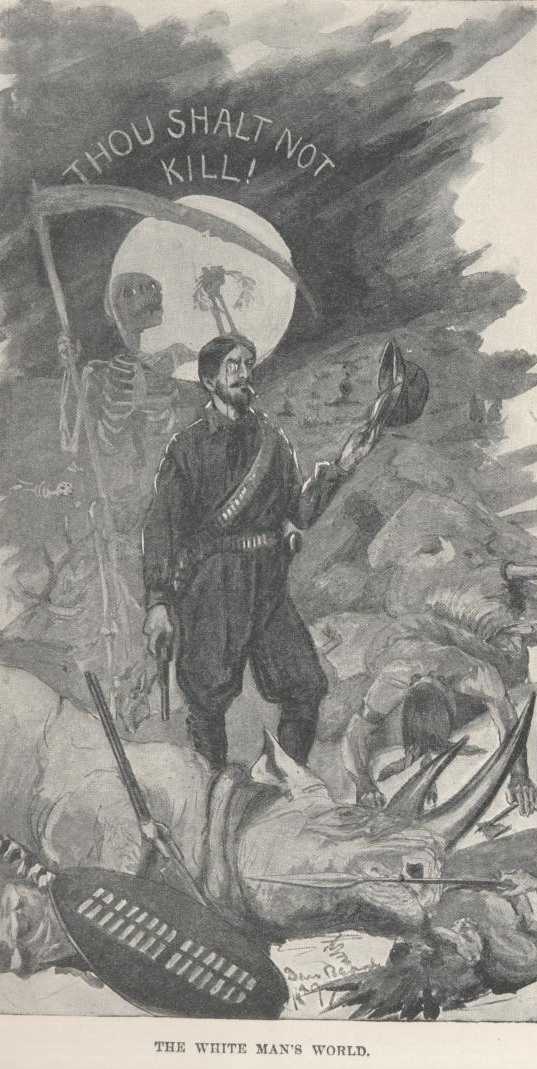

“The White Man’s World.” Illustration from Following The Equator. Chpt. XIX, p.187.

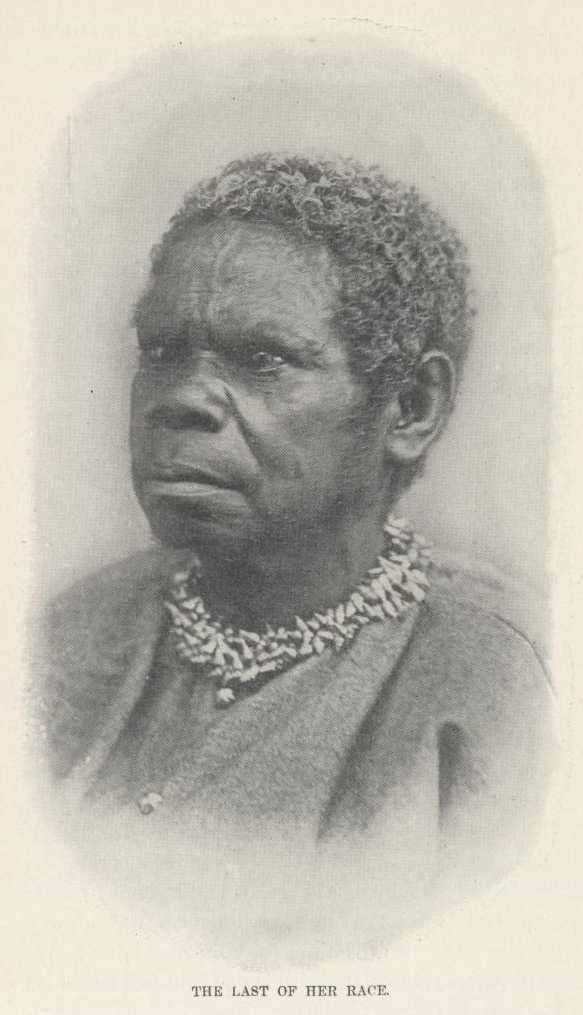

Still, Twain knows that his readers will be most comfortable if he frames his recounting of historical genocides within narrative forms that they already know. His recounting of Tasmania’s “Black Wars” is taken almost entirely from written sources sympathetic to the Tasmanians, and he ends those chapters with a lament about the last of the Tasmanians that comes straight out of U.S. romantic literature about the “passing” of the Noble American Indian. On the one hand, his ability to manipulate his sources in order to play to his white readership’s varying comfort levels shows his mastery of travel literature’s protocols; on the other hand, the shocking amount of inconsistency in his attitudes towards settlers’ treatments of native populations suggests that even as he observed those protocols, he was beginning to realize just how much brutality went into the formation of the British Empire, especially among settler colonies like Australia, Tasmania, and South Africa. Researching and composing the story of settler atrocities forced him to a rare confession of his personal point of view, namely, that “There are many humorous things in the world; among them the white man’s notion that he is less savage than the other savages” (213).

Despite these very problematic instances, there is much to enjoy in Following the Equator. The Australia section renders interesting historical glimpses into the colonials’ lives, customs, and architectures, as well as glimpses into the colony’s convict history. Twain also delves into Australians’ uses of the English language, delighting in their accents and in their incorporation of Aboriginal words into placenames. At one point he lists three columns of place names, then fashions a poem from them, its rhythms reminiscent of Kipling’s romping verses. Titled “A Sweltering Day in Australia,” the 10th stanza gives a good snapshot of his delight (not to speak of his physical discomfort):

Cootamundra, and Takee, and Wakatipu,

Toowoomba, Kaikoura are lost!

From Onkaparinga to far Oamaru

All burn in this hell’s holocaust! (Following The Equator, p.328)

“The Last of Her Race.” Photograph from

Following The Equator. Chpt. XXVII, p.266

At the conclusion of the 12 stanzas Twain opines, “these are good words for poetry. Among the best I have ever seen. There are 81 in the list. I did not need them all, but I have knocked down 66 of them; which is a good bag, it seems to me, for a person not in the business. … The best word in that list, and the most musical and gurgly, is Woolloomoolloo. It is a place near Sydney, and is a favorite pleasure-resort. It has eight O’s in it” (330).

This was neither Twain’s first nor last attempt at poetry, but it remains one of his best, especially for what it reveals of a master wordsmith’s reveling in the possibilities of polysyllabic languages.

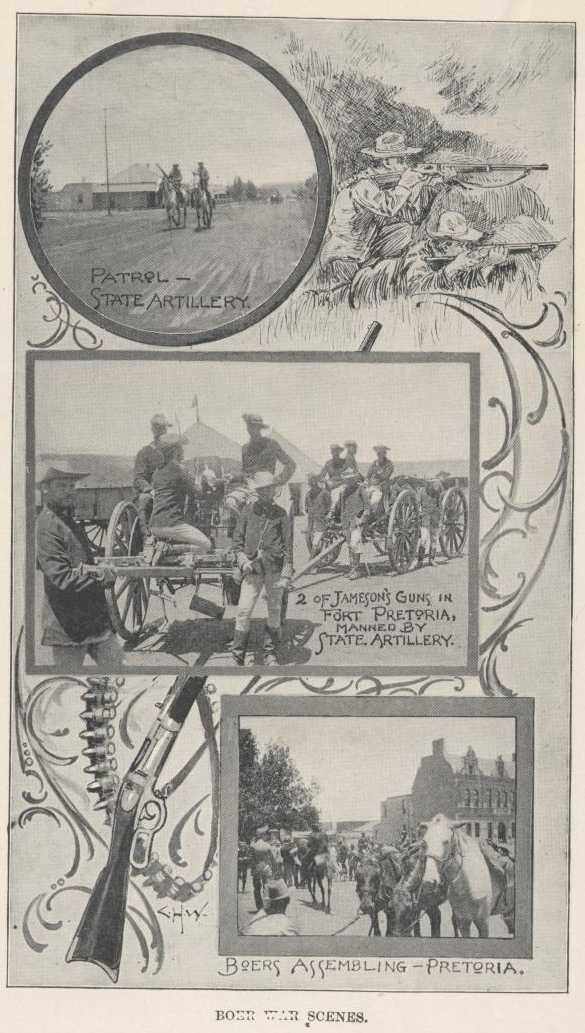

The South Africa portion of Following is the shortest, primarily because Twain was forced to cut large sections in order to keep the book to one volume. Nevertheless, it gives us a good snapshot into English settler life in that very multi-ethnic society. In addition to information about diamond mining, the section is largely devoted to trying to understand British/Boer relations—the “Jamison Raid,” during which a small group of British settlers attempted to overthrow Boer control of the Transvaal–occurred just before Twain’s visit to Johannesburg, and he devotes several chapters to figuring out who the Raiders were and why they thought they could succeed. [iii] Although he largely refrained from commenting on local politics throughout Following the Equator, in the South Africa section of the book he does not suppress his hostility to Cecil Rhodes, British South Africa’s Prime Minister from 1890-1896. Concluding a long paragraph in which he marvels at Rhodes’ success at maintaining the loyalty of people who openly acknowledge Rhodes’ attempts to undermine British laws, garner riches from the public coffers, and brutally suppress the native African population, Twain comments,

He [Rhodes] has done everything he could think of to pull himself down to the ground; he has done more than enough to pull sixteen common-run great men down; yet there he stands to this day, upon his dizzy summit under the dome of the sky, an apparent permanency, the marvel of the time, the mystery of the age, an Archangel with wings to half the world, Satan with a tail to the other half.

I admire him, I frankly confess it; and when the time comes I shall buy a piece of the rope for a keepsake (Following The Equator, p.710).

“Boer War Scenes.” Image from Following

The Equator. Chpt. LXVI, p.664.

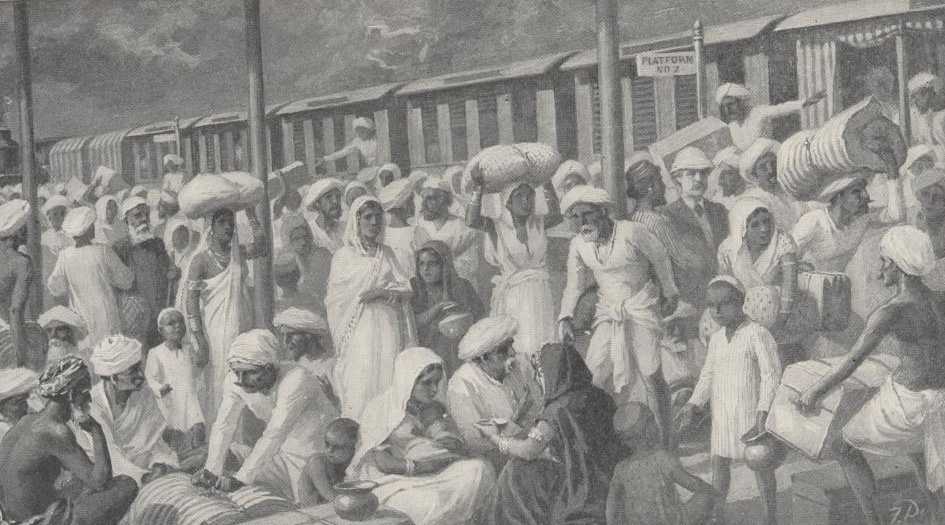

Of all the places Twain visited on this lecture tour, India fascinated him the most. For him as for most Westerners, even now, India epitomized the foreign and the exotic. Twain excels at both landscape description and word-portraits of groups of people, and Following has many passages of the latter. Inside the railway station in Bombay (now Mumbai), for instance, he marvels, as he does throughout India, at the number, variety, and dress of the people flowing past him.

Inside the great station, tides upon tides of rainbow-costumed natives swept along, this way and that, in massed bewildering confusion, eager, anxious, belated, distressed; and washed up to the long trains and flowed into them with their packs and bundles, and disappeared, followed at once by the next wash, the next wave. And here and there, in the midst of this hurly-burly, and seemingly undisturbed by it, sat great groups of natives on the bare stone floor,–young, slender brown women, old gray, wrinkled women, little soft brown babies, old men, young men, boys; all poor people, but all the females among them, both big and little, bejeweled with cheap and showy nose-rings, toe-rings, leglets, and armlets, these things constituting all their wealth, no doubt. These silent crowds sat there with their humble bundles and baskets and small household gear about them, and patiently waited—for what? A train that was to start at some time or other during the day or night! They hadn’t timed themselves well, but that was no matter—the thing had been so ordered from on high, therefore why worry? There was plenty of time, hours and hours of it, and the thing that was to happen would happen—there was no hurrying it (Following The Equator, 403-04).

“A Railway Station.” Illustration from Following The Equator. Chpt. XLIV, p.402.

Passages like this highlight Mark Twain’s brilliance at constructing long, complex sentences that flow like the scenes he describes. Parsing Twain’s paragraphs provides lesson plans in themselves: how and when to use adjectives and adverbs; how to vary long and short sentences, and above all, how to use semicolons!

Humorous passages also lace Following the Equator. The final section of Chapter 39, which recounts a visit from the Aga Khan [iv], is not without racial stereotyping, but it also shows how Twain can turn a simple visit into a hilarious sketch. It is also a passage where he makes fun of himself, as a famous writer feigning modesty. In the sketch, his fez-wearing Indian servant, whom he has nicknamed “Satan” because he cannot pronounce the man’s Indian name, announces that,

“’God want to see you.’

‘Who?’

‘God. I show him up, master?’

‘Why, this is so unusual, that –that—well, you see–Indeed, I am so unprepared—I don’t quite know what I do mean. Dear me, can’t you explain? Don’t you see that this is a most ex—’

‘Here his card, master.’

Wasn’t it curious—and amazing, and tremendous, and all that? Such a personage going around calling on such as I, and sending up his card, like a mortal—and sending it up by Satan. It was a bewildering collision of the impossibles. But this was the land of the Arabian Nights, this was India! And what is it that cannot happen in India?” (Following The Equator, 368)

Here Twain’s rendering of his servant’s rudimentary English, his own fragmented, flustered, response; his reference to being “unprepared” for God’s visit, and his reference to India as the land where the impossible happens, would have all been familiar to his readers from novels, sermons, “ethnic” sketches, and popular depictions of the subcontinent. We can’t know if Twain himself was aware that Muslims do not have gods, and that the young man visiting him was revered because he was a descendant of Mohammad and as such, spiritual leader of the Ismaili Muslims, but not a god. The narrator’s assumption that the Aga Khan is a god is integral to the joke; he marvels when his visitor speaks excellent English and is stunned when the Aga Khan renders “a compact and nicely-discriminated literary verdict” on Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The sketch is much more about Twain’s ego than about his visitor’s eminence; as the young man discourses on Twain’s novel, the author marvels:

I had had my ambitions—I had hoped, and almost expected, to be read by kings and presidents and emperors—but I had never looked so high as That. It would be false modesty to pretend that I was not inordinately pleased. I was. I was much more pleased than I should have been with a compliment from a man (Following The Equator, 367).

The sketch closes with a twist that is pure Twain. At the end of the half hour interview, as the Aga Khan “rose to say good-bye,”

The door swung open and I caught the flash of a red fez, and heard these words, reverently said—

‘Satan see God out?’

‘Yes.’ And these mis-mated Beings passed from view—Satan in the lead and The Other following (Following The Equator, 368).

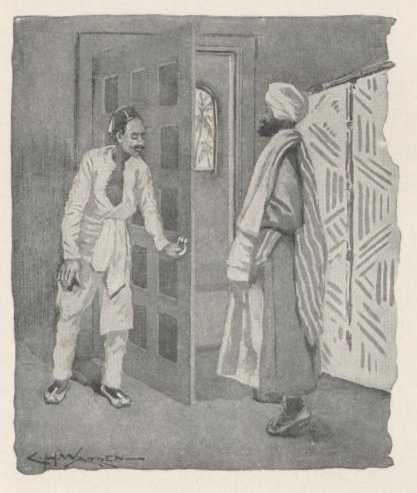

Illustration of Satan Seeing God Out.

From Following The Equator. Chpt. XXXIX, p. 368.

Following the Equator has never been Twain’s most popular travelogue, in large part because of its disjointedness. Nevertheless, it contains valuable insights into the lives, customs, and world-views of British settlers across a wide swath of the Empire in the late 19th century; historical accounts of now almost-forgotten events; meditations on colonial/Indigenous relations, and portraits of Indigenous lives, that tell us a great deal about Western culture at the turn into the 20th century. Looking backward, we can also trace some of the threads that remain with us today. I have mined chapters for teaching, and passages for public readings, and continuing scholarly research is uncovering contexts and contemporary documents that increase our grasp of Twain’s own viewpoints as he was composing the text. For art historians, the drawings and photographs provide insight into how editors and prominent illustrators interpreted Twain’s words. It is a book well worth visiting, both for its portraits of the past, and for its insights into a world order whose shadows still hover.

[i] All quotations from Following the Equator refer to the Dover paperback edition, first published in 1989. The Dover edition is a reprint of the first, 1897 edition published by The American Publishing Company, Hartford, Connecticut.

[ii] At the time, Tasmania was a separate, self-governing colony, part of the British Empire but not yet part of Australia. When the Australian states joined together to form the Commonwealth of Australia 1901, Tasmania united with them, becoming, in effect, an Australian state.

[iii] European appropriation of land in what is now South Africa began with Dutch settlers in the 17th century. Pushed northward by British invasions in the early 19th century, the Dutch settlers, known as Boers, established the Boer Republic in the area known as the Transvaal. Fighting over the areas’ diamond and gold reserves, as well as its arable land, was frequent. At the time of Twain’s visit, the British Cape Town Colony, then headed by Cecil Rhodes, and the South Africa (Boer) Republic, headed by Paul Kruger, had already fought what became known as the First Boer War, which ended with Boer victory. The Second Boer War of 1899 ended with British control, and the British and Boer areas were united as the Union of South Africa in 1909.

[iv] aka Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah.

Suggested Further Readings

- Bridgman, Richard. Traveling in Mark Twain. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Cooper, Robert. Around the World with Mark Twain. New York: Arcade, 2000.

- Driscoll, Kerry. Mark Twain among the Indians and Other Indigenous Peoples. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.

- Harris, Susan K. Mark Twain, the World, and Me: Following the Equator, Then and Now. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2020.

- Melton, Jeffrey A. Mark Twain, Travel Books and Tourism: The Tide of a Great Popular Movement. University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- Messent, Peter. “Racial and Colonial Discourse in Mark Twain’s Following the Equator.” Essays in Arts and Sciences 22 (October, 1993): 67-83.

- Philippon, Daniel L. “Mark Twain in South Africa, Day by Day.” Mark Twain Journal 40, no.1 (Spring 2002): 14-24.

- Schillingsburg, Miriam Jones. At Home Abroad: Mark Twain in Australasia. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1988.

- Strathcarron, Ian. The Indian Equator: Mark Twain’s India Revisited. Mineola, NY: Dover, 2013.

- Wetzel, Betty. After You, Mark Twain: A Modern Journey around the Equator. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1990.

- Zacks, Richard. Chasing the Last Laugh: Mark Twain’s Raucous and Redemptive round-the-World Comedy Tour. New York: Doubleday, 2016.

About the Author

Susan K. Harris has served on the faculties of the University of Kansas, Penn State, and Queens College, CUNY. Her specialties are Mark Twain Studies and Studies of American Women Writers. Among her six monographs are Mark Twain’s Escape from Time: A Study of Patterns and Images (U Missouri P, 1982); The Courtship of Olivia Langdon and Mark Twain (Cambridge, 1996); and God’s Arbiters: Americans and the Philippines, 1898-1902 (Oxford, 2011). She has edited three American women’s novels for Penguin/Putnam Press, the Library of America’s volume of Twain’s historical romances, and a Houghton Mifflin pedagogical edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Her most recent work is Mark Twain, The World, and Me (U Alabama P, 2020). Retired, she lives and writes in Brooklyn, NY.

Professor Harris has participated in a number of CMTS events and given numerous lectures, including:

- Susan K. Harris, Interview about her book Mark Twain, The World, and Me (October 21, 2020)

- Susan K. Harris, “Searching For The Ornithorhynchus: Mark Twain and Animal Conservation” (October 7, 2015 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Susan K. Harris, “Mark Twain and the Philippine-American War: “Hogwash” and “Pious Hypocrisy” (May 30, 2012 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Susan K. Harris, “Love Texts: The Role of Books in the Courtship of Olivia Langdon and Mark Twain” (November 13, 1996 – Quarry Farm)

- Susan K. Harris, “Olivia Langdon Clemens’s Reading” (April 29, 1992 – Quarry Farm)

- Susan K. Harris, “Overcoming Sin: The Audiences for Mark Twain’s ‘Hadleyburg’” (July 23, 1990 – Quarry Farm)

- Susan K. Harris, “Four Ways to Kill a Mackerel: Mark Twain and Laura Hawkins” (November 3, 1988 – Quarry Farm)