Life on the Mississippi

Samuel Clemens’s childhood in Hannibal and his career as a steamboat pilot in his early twenties established the importance of the Mississippi River to him during his formative years. Without those experiences, it’s a safe bet that we wouldn’t have Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In light of the river’s influence on Mark Twain, it’s somewhat surprising that Life on the Mississippi has been relatively overlooked. For years, when this travel book has received attention, a majority of critics discounted it as a disappointment. I argue that this assessment is short-sighted; it’s clear that Twain took this work very seriously, asserting in the book’s opening sentence, “The Mississippi is well worth reading about.” [i] This is not an idle claim; the river as a topic had long attracted his attention. His desire to write a Mississippi book gestated for almost two decades before it came to pass. In an 1866 letter to his mother, he alludes to a secret plan for a book of some 300 pages, the last third of which will have to be completed in St. Louis, which the editors of the Mark Twain Project note was a book about the Mississippi. [ii] In a letter to his wife Oliva five years later, he explicitly mentions his intention to write a “standard work” on the mighty river. [iii] He predicts that the project will include two months of traveling on the river, “and then look out!”—which comes close to what his 1882 Mississippi research trip entailed, about a decade after his letter to Olivia.

Life on the Mississippi (1887) first edition

Mark Twain’s Idiosyncratic Method

It was rare that Mark Twain wrote any of his longer works in one go. Usually, his composition was interrupted by periods of neglect, and in some cases these hiatuses were long. Life on the Mississippi falls into the latter category. As a result of its prolonged development, the book evolved into a project rather distinct from his other travel books. Indeed, the original composition of Life on the Mississippi did not involve a trip to the river; instead, it was a seven-part series of reminiscences of his days as a cub-pilot on Mississippi steamboats, which appeared in the Atlantic from January to August 1875 (with no installment published in the July issue). Yet even this successful magazine series came about nearly by accident. In 1874, Mark Twain made his debut in the Atlantic with “A True Story Repeated Word for Word as I Heard It.” William Dean Howells, editor of the magazine who would become Twain’s lifelong friend and literary sounding board, admired the vernacular authenticity and dramatic effect of Twain’s story of a formerly enslaved woman who recounts her reunion with her adult son who had been sold away from her as a young child. And Howells asked Twain if he had anything else for the Atlantic. Eager to capitalize on his first flush of success in the prestigious magazine, Twain mulled the offer over for several weeks only to admit to Howells that he would not be able to take advantage of the opportunity. On the same October afternoon when Twain sent his letter of demurral, he was on a routine walk with his friend and Hartford minister Joseph Twichell. Their conversation led to Twain recollecting his early career as a Mississippi steamboat pilot, to which Twichell exclaimed, according to Twain, “What a virgin subject to hurl into a magazine!” [iv] Suffused with confidence about the merits of this idea, Twain hurried home to write Howells, telling him to disregard his earlier letter and promising him that he would not only have an article for the Atlantic’s January 1875 issue, but an entire series. Convinced that he was uniquely equipped to provide vivid accounts of the romance of riverboat piloting, Twain promised Howells as many as nine installments; the seven that he produced would appear under the title “Old Times on the Mississippi.” The sketches were greeted warmly by readers of the magazine, as well as those of New York, St. Louis, and San Francisco periodicals where the series was pirated them. The success of “Old Times” provided Twain the confidence to return to the stalled manuscript of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which led directly into Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Mark Twain, circa 1880.

Still, Twain’s most celebrated novel also hit a snag about one-third of the way into the narrative. Pigeon-holing the manuscript for several years, Twain turned to other works, most notably Life on the Mississippi. After a research trip on the river in 1882, the year of a 100-year flood, Twain recommenced work on the book-length project in 1882-1883. He began by dividing the seven Atlantic sketches into chapters 4-17, framing these with three chapters before and three after, and then pivoting to 40 chapters of primarily contemporary observations that he had made during the 1882 return trip on the river. Like some of Twain’s other travel books, Part 2 is composed of seemingly random observations. The loose narrative of the trip documents the changes in the river and the life of its communities, as well as commentary on the river taken from other published sources. The text’s bifurcated structure of personal reminiscences from the antebellum period and the pastiche of observations from 1882 reflect the shift in literary tastes from the romanticism that prevailed prior to the Civil War and the realism that characterized the national ethos after it.

Critical Assessments

The humor, nostalgia, and personal voice of the “Old Times” sketches have led most critics to praise the first portion of the book and to judge the balance of the book as not only a disappointment but a failure. Prompted by the value accorded to organic unity by New Criticism of the early and mid-twentieth century, these assessments presumed that Twain’s intention in Life on the Mississippi was something quite different from what the text shows us that it is. For Life on the Mississippi is deliberately not unified, nor was the nation that inspired it. In other words, the critical assumption that the book’s two halves are at crossed purposes is predicated on the idea that Mark Twain had one purpose. The text, however, provides countervailing evidence.

Additionally, critics in this camp surmise that Twain was beholden to the requirements of the subscription publication, that his contract demanded a certain number of words to yield a book of substantial heft. This obligation, it has often been suggested, led him to import as many as 10,000 words copied from other sources, most of which appear in Part 2 of the volume. The allegation that Twain desperately imported seemingly random information from other sources simply to fulfill the word count of subscription publishing has been offered as evidence to support the claim that Twain made an already bad design decidedly worse. However, this charge ignores the fact that he had excluded more than 15,000 words of original composition from the final manuscript. If the length required by subscription publishing was the driving motivation, he had no need to introduce material from other sources. Clearly, though, he made a choice to exclude those 15,000 of his own words and to rely on information from others who had written about the river and its inhabitants at various points in the history of the North American continent. That compositional decision refutes the basis of this particular disparaging criticism. Something else is going on in the motley composition Life on the Mississippi than simply fulfilling a contract.

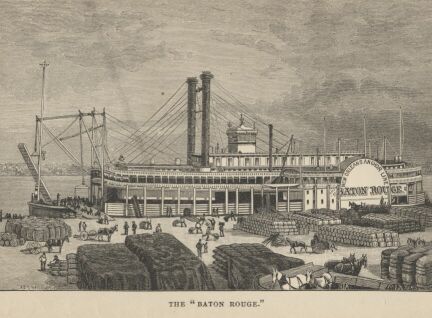

“The ‘Baton Rouge.'” Illustration from Life on the Mississippi (1883) Frontispiece.

Sam Clemens, Pilot; Mark Twain, Writer

Because Life on the Mississippi was written at two different times, corresponding to two different periods in Twain’s life, the divergent modes of the “Od Times” chapters and the travel account in the subsequent chapters register a shift in Twain’s professional identity. Although he was a writer when he composed “Old Times,” his focus in the sketches is on how he became a Mississippi steamboat pilot. That is, Part 1 of the book reflects his youthful aspiration and subsequent participation in the profession of steamboat piloting. His first fascination with steamboat life is inspired by the vitality he perceives in the vigorous, authoritative language of steamboatmen. Early on, he describes being in awe of the blustery orders of the steamboat’s mate, “discharged … like a blast of lightning, and sen[ding] a long, reverberating peal of profanity thundering after it.”[v] He provides a sample of such forceful speech and confides, “I wished I could talk like that.” [vi]

He soon recognizes that the real authority speech is that of the steamboat pilot, who commands from on high in the pilothouse and who answers to no one—a romantic figure if ever there was one. Seeking to join this august fraternity, he signs on as an apprentice to a celebrated pilot, Horace Bixby. Despite being 22-25 years old during this period, Twain portrays himself as a naïve adolescent, a far cry from the young man who had begun to enjoy a more cosmopolitan outlook while supporting himself for about seven years in the print shops of major cities like Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and New York. In his cub-pilot memoir, he depicts his apprenticeship as a series of humiliating trials from which he gradually develops expertise. But this achievement comes at a price. In a famous passage, Twain recounts how his piloting education had deprived him of his ertstwhile aesthetic appreciation of the riverscape:

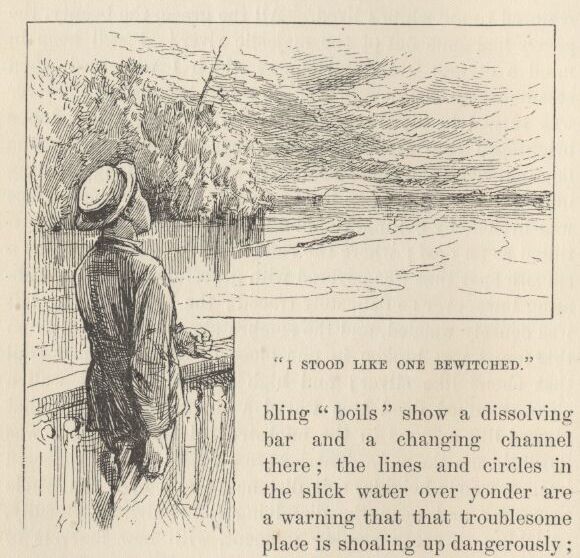

Now when I had mastered the language of this water and had come to know every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. I had lost something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry had gone out of the majestic river! I still keep in mind a certain wonderful sunset which I witnessed when steamboating was new to me. A broad expanse of the river was turned to blood; in the middle distance the red hue brightened into gold, through which a solitary log came floating, black and conspicuous; in one place a long, slanting mark lay sparkling upon the water; in another the surface was broken by boiling, tumbling rings, that were as many-tinted as an opal; where the ruddy flush was faintest, was a smooth spot that was covered with graceful circles and radiating lines, ever so delicately traced; the shore on our left was densely wooded, and the somber shadow that fell from this forest was broken in one place by a long, ruffled trail that shone like silver; and high above the forest wall a clean-stemmed dead tree waved a single leafy bough that glowed like a flame in the unobstructed splendor that was flowing from the sun. There were graceful curves, reflected images, woody heights, soft distances; and over the whole scene, far and near, the dissolving lights drifted steadily, enriching it, every passing moment, with new marvels of coloring. I stood like one bewitched.

–Life on the Mississippi (1883), chpt.9, p.119

“I Stood Like One Bewitched.” Illustration from Life on the Mississippi (1883), Chpt.9, p.120.

After describing how he had once marveled at a radiant Mississippi sunset, he admits that such a breathtaking spectacle no longer moves him: “No, the romance and the beauty were all gone from the river. All the value any feature of it had for me now as the amount of usefulness it could furnish toward compassing the safe piloting of a steamboat.” [vii]

If the pilot’s job prioritizes usefulness, enabling him to deliver his passengers and cargo expediently and without incident, the writer’s task is just the opposite. A vibrant narrative needs conflict, unexpected plot twists, vivid characters, and the indulgence of picturesque detail—the very elements that Sam Clemens’s steamboat experience had taught him to ignore. Twain subtly underscores this point in describing the experience of the citizens of Vicksburg who endured a six-week siege in 1863 by Union troops. Twain notes that the experience rendered the survivors incapable of telling their story with any vitality:

A week of their wonderful life there would have made their tongues eloquent forever perhaps; but they had six weeks of it, and that wore the novelty all out; they got used to being bomb-shelled out of home and into the ground; the matter became commonplace. After that, the possibility of their ever being startlingly interesting in their talks about it was gone.

–Life on the Mississippi (1883), chpt.XXXV, p.379

In contrast to the Vicksburghers, a man with only cursory knowledge of the Civil War whose imagination and storytelling talent would not silenced by overwhelming experience—a man much like himself.

Granted the “Old Times” sketches include plenty of the kinds of interesting elements that he claims to have forfeited as a pilot. But as his piloting career came to an end, he wound his way into a new one that granted him restored his narrative ability. He notes in Chapter XXI, “by and by the war came, commerce was suspended, my occupation was gone.”[viii] He then enumerates the variety of other livelihoods he has pursued: “silver miner in Nevada,” “newspaper reporter,” “gold miner in California,” “reporter in San Francisco,” “special correspondent in the Sandwich Islands, “roving correspondent in Europe and the East,” “instructional torch-bearer on the lecture platform,” and “finally a scribbler of books,” a professional trajectory that readers familiar with Innocents Abroad and Roughing It would have recognized. Two aspects of this personal account are noteworthy: first, the importance of Chapter 21 in encapsulating his career during the twenty-one years during which he has been absent from the Mississippi, which the correspondence of the chapter number and the duration of his absence subtly suggests; and second, the arc of his experience has resulted in him becoming a “scribbler of books.” In other words, he composes Part 2 of Life on the Mississippi not as a former pilot as in Part 1, but as a writer. And the focus of his attention in the travel narrative is not primarily recollection; it is observation about the changes, first, in steamboating and piloting, and, second—and in the country itself.

The New South on the Mississippi

Twain’s subtle mention, “by and by the war came,” understates how cataclysmic the Civil War was in the history of the United States. Not only was his occupation gone, but the nation became immersed in violence and death. And, of course, the war didn’t just come and go; its effects endured. Twain notes that, unlike the Vicksburg siege survivors, many Southerners persist in talking about the Civil War.

In the North one hears the war mentioned, in social conversation, once a month; sometimes as often as once a week, but as a distinct subject for talk, it has long ago been relieved of duty. … The case is very different in the South. . . . [T]he war is the great chief topic of conversation. The interest in it is vivid and constant; . . . Mention of the war will wake up a dull company and set their tongues going . . . In the South, the war is what A.D. is elsewhere: they date from it. All day long you hear things “placed” as having happened since the waw; or du’in’ the waw; or befo’ the waw; or right aftah the waw; or ‘bout two yeahs or five yeahs or ten yeahs befo’ the waw or aftah the waw.

–Life on the Mississippi (1883), chpt.XLV, p.454

Although, Twain’s references to the Civil War throughout Life on the Mississippi are relatively few, his assertion “by and by the war came” encourages us to see that brief three-paragraph chapter not just as a transition between the reminiscences of piloting in Part 1 and the travel narrative of Part 2, but also as the kind of pivot point that A.D. is in the historical understanding of Western culture and that the Civil War is for people in the South. For Samuel Clemens, the importance of the war in the national consciousness is a source of personal embarrassment because he opted not to participate in the most crucial event in American history to that point, a defining event for those of his generation. Instead, in 1861, he accompanied his brother Orion to Nevada where Orion had been appointed territorial secretary. Upon revisiting the South in his 1882 river trip, he was both reminded of how the war had changed country had changed and how it hadn’t. The South’s fixation on the war was a result of its impact on their lives, undoubtedly. But Twain blurs the source of the conflict by contending that the war itself was the consequence of the South’s romantic temperament. Where in “Old Times” Twain himself romanticized the pilot as a kind of nobility, in Part 2 he criticizes the South for having fallen for the romanticism of Sir Walter Scott, stunting the region’s cultural growth and preventing it from entering the modern age. In Twain’s account of history, it was not slavery but a misguided literary appreciation that put the South at odds with the progressive North.

Conversely, Twain’s account of the river and its surrounding communities are plagued by his sense that the splendor of “Old Times” has vanished. Railroads have outcompeted steamboats, whose remaining relics show neglect rather than the grandeur of his piloting days. And the expertise of piloting has been minimized by the work of the Army Corps of Engineers whose navigational improvements reduced the once lofty pilot to a mere steersman. Meanwhile, an aggressive commercial attitude has infected contemporary society, with slick salesmen and con artists in abundance. No doubt, a similar avarice had been prevalent in the earlier period, but with piloting demanding his attention, Twain didn’t notice. As a passenger-observer in 1882, he is struck by the ways in which “the dollar [has become a] god; how to get it [a] religion” in the postbellum era. [ix] In characteristic self-effacing fashion, he includes himself in the critique of greed in an extended tale about his anticipation of finding a buried treasure in Napoleon, Arkansas, which Karl Ritter, whom Twain had met in Germany years before, confided to him in a death-bed revelation. The suspense builds as the steamboat nears Napoleon, only to have Twain’s high hopes deflated upon learning that the town of Napoleon had been destroyed by a flood in the interim. Still, this disappointing fact dovetails with another theme—the inevitability of the river, a natural force, to resist human objectives. Although engineering improvements like lighting and levees have made navigation easier, these interventions are merely temporary. The river’s indifference to the ways of man will always prevail.

Twain is surprisingly silent about the end of Reconstruction, which lurks in the background of the travel narrative. Indeed, in an observation that he deleted from the manuscript, he claims, “I missed one thing in the South—African slavery. That horror is gone, and permanently.”[x] Adding to the texts problematic framing of race are illustrations, particularly those on pp. 368, 370, and 371 by A. B. Shute, a staff artist for publisher James Osgood. But Mark Twain knew better than he lets on. In 1876, Southern Democrats had leveraged the deadlock of the Hayes-Tilden election to end Reconstruction in exchange for ceding the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes. Having married into a progressive family—the Langdons of Elmira had been active in the Underground Railroad and instrumental in Frederick Douglass’s flight to freedom —Twain was fully aware of the turn of late-nineteenth-century politics, and commented explicitly in his notebooks about Andrew Johnson’s betrayal of the cause of Black rights. He met Douglass through the Langdons and first heard the famous civil-rights activist speak at an 1880 Emancipation Day celebration in Elmira, in which he addressed the racial injustices of post-Reconstruction America.[xi]

Illustation from Life on the Mississppi (1883),

Chpt.33, p.371

“A Plain Gill.” Illustration from Life on the Mississippi (1883), Chpt.33, p.370.

Thus, on his return to the Mississippi in 1882 Twain must have witnessed what he already knew about the South’s retrenchment into white supremacy through Jim Crow laws that turned back the progress of the Reconstruction amendments to the US Constitution. And he also knew that the South’s official acts were augmented by vigilante terror campaigns aimed at intimidating Blacks who sought to exercise their rights. Upon arriving in New Orleans, Twain established a close friendship with the Louisiana writer George W. Cable, an outspoken Southerner who three years later would pointedly criticize his region’s tyranny in famous essays, “The Silent South” and “A Freedman’s Case in Equity” (1885). Although we don’t know if Twain witnessed first-hand the New South’s racial discrimination, it is probable that this visit influenced the ending of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. For although Twain’s most celebrated novel is nominally about slavery, a story about slavery had limited relevance in 1885. Whereas, reading Tom Sawyer’s machinations in “freeing a free Negro” against the backdrop of the Jim Crow South suggests that Twain is satirizing the degrading racism of the region. Indeed, for those who have pondered why Twain would have Huck and Jim travel south, a plausible explanation is that the South is where white antagonism toward Black liberation persisted and needed to be addressed. Twain may not have realized it when he began composing Huckleberry Finn in 1876, but by the time he resumed writing it in 1883 after completing Life on the Mississippi, it seems highly likely that he would have recognized the opportunity that their southward journey afforded him.

The Mississippi and History

Despite Twain’s distorted analysis of the Civil War as a literary problem, Life on the Mississippi is concerned very directly with history—Sam Clemens’s personal history, certainly, but also the river’s history and the development of North America as a site of Western expansion and the cultural erasure of the continent’s first inhabitants. The book’s first two chapters draw on Francis Parkman’s canonical history of North American exploration, but Twain’s subtle ironic commentary destabilizes the authority of the portions of Parkman’s account that he quotes. In effect, he calls into question Parkman’s celebration of the voyages of DeSoto and LaSalle for having served the rapacity of European monarchs, like LaSalle’s patron, whom Twain mocks as “Louis the Putrid.” In the very next chapter, Twain turns away from official historical interpretation and offers instead a section originally written for Huckleberry Finn. Huck’s account of the loudmouthed rants and vernacular boasts of Mississippi raftsmen counterbalances the lofty grandeur of Parkman’s history and signals the kind of materials that Life on the Mississippi will include.

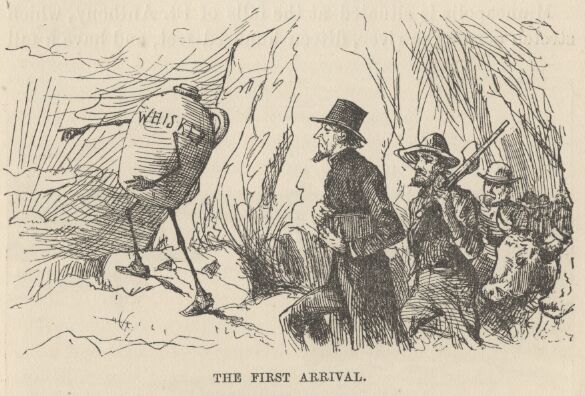

Indeed, in the book’s later chapters, as Twain voyages north from Hannibal toward the Mississippi’s headwaters, he implicitly recalls the jug-passing colloquy of Huckleberry Finn’s raftsmen’s passage in Chapter 3, contending that the so-called progress of Western civilization can be traced to whiskey. Revising Berkeley’s confident slogan about the advantages of English colonization of North America, Twain quips, “Westward the Jug of Empire takes its way.”[xii] His implication is that Western civilization has proceeded from corruption and gained its hold over those it has dominated (if not eradicated) by inducing their corruption. Countering the official erasure of indigenous voices, Twain introduces Native American legends, reminding us that the source of the Mississippi and the oral histories of the first inhabitants of America have parallel origins.

“The First Arrival.” Illustration from Life on the Mississippi (1883), chpt.60, p.587.

Thus, by abandoning the personal reminiscences of “Old Times” for a more diverse verbal texture, Twain presents a more comprehensive account of American life, one that includes a motley array of characters, dialects, and stories. Running the gamut from Gothic to heroic, canonical to folkloric, from serious to humorous, from confidence schemes to picturesque lies, Life on the Mississippi celebrates the full range of American culture—standard and vernacular– without apology. And here, Twain’s purpose of including materials from other published sources becomes clear. Much like the quotations from Parkman, Twain’s borrowed sources provide a polyphonic texture that while uneven bristles with variety and complexity.

The Plurality of Life on the Mississippi

To conclude, it seems necessary to acknowledge that the critics who viewed Part 2 as characterized by a structural looseness were not wrong. But they were mistaken in thinking that Twain missed his target. The structure of the travel narrative is, like many of his other travel writings, a match for his professional identity as a “scribbler.” For in Twain’s writing, the traveling scribbler may follow the sequence of a journey, but his goal is not to restrain his observations but to allow them to wander. The traveling scribbler delights in the snags and eddies of narrative for the picturesque variety they lend to the experience. By turning away from the comparatively tighter control employed in “Old Times,” Twain allowed an associative logic to permeate the Mississippi book’s travel narrative, one in which subtle references in one topic can catalyze a link to another.

This method foreshadows the one he would theorize and apply in writing his autobiography. In 1904, he describes his discovery of

the right way to do an Autobiography: Start it at no particular time of your life; wander at your free will all over your life; talk only about that thing which interest you for the moment; drop it the moment its interest threatens to pale, and turn your talk upon the new and more interesting thing that has intruded itself into your mind meantime.

– Mark Twain. The Autobiography of Mark Twain. 3 vols. Eds. Harriet Elinor Smith, et al. Berkeley: U California P, 2010- 2015. I: 220.

The result of such free play is not chaos but what he called an “apparently systemless system—only apparently systemless, for it is not that . . . [it] is a system which is a complete and purposed jumble – a course which begins nowhere, follows no specified route, and can never reach an end.” [xiii] These later considerations about the form of autobiography may not have been on Twain’s mind when composing Life on the Mississippi, and the account Mississippi journey does have a course but a meandering and digressive one, but the autobiographical “system” he describes was, nonetheless, formally appropriate to a book about the great, ever-flowing, and ever-shifting river that informed so much of Mark Twain’s early life.

Indeed, even before he articulated these ideas in 1904, Howells had celebrated this quality of Twain’s prose: “So far as I know, Mr. Clemens is the first writer to use in extended writing the fashion we all use in thinking, and to set down the thing that comes into his mind without fear or favor of the thing that went before of the thing that may be about to follow.”[xiv] Howells credits Twain for latching on to materials from “that divine ragbag that we call the mind, and leav[ing] the reader to look after relevancies and sequences for himself, . . . [to] shift . . . responsibility to the reader, with whom it belongs, at least as much as with the author.” [xv] Twain’s claim that his autobiographical method is one in which “the past and the present are constantly brought face to face, resulting in the contrasts which newly fire up the interest all along like contact of flint and steel” is an appropriate description of the conceptual premise of the Mississippi book divided into halves that deal with his reminscences of the past and his remarks about the present.[xvi] Life on the Mississippi, a book about a river that “is well worth reading about,”—and then some—brings together Twain’s piloting past with his writerly present illuminating the combustible contrasts inherent in its structure.

[i] Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (1883), New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. P. 20. Subsequent references are to this edition and will appear parenthetically in the text.

[ii] Letters of Mark Twain, SLC to Jane Lampton Clemens, January 20, 1866. Marktwainproject.org.

[iii] Letters, SLC to Olivia Langdon Clemens, November 27, 1871. marktwainproject.org.

[iv] Letters, SLC to W.D. Howells, October 24, 1874. marktwainproject.org.

[v] LOM, p. 75.

[vi] LOM, p. 76

[vii] LOM, pp. 120-21.

[viii] LOM, p.245

[ix] LOM, p.412

[x] See Life on the Mississippi. New York: Penguin, 1984, p. 332. This edition, edited by John Seelye, includes “suppressed” passages.

[xi] Frederick Douglass, “The Lessons of Emancipation To The New Generation,” (August 3, 1880). Center for Mark Twain Studies, MarkTwainStudies.com/LessonsOfEmancipation/[

[xii] LOM, p.587.

[xiii] The Autobiography of Mark Twain. I: 441.

[xiv] William Dean Howells. “Mark Twain: An Inquiry” (1901). In My Mark Twain. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1910. Pp. 166.

[xv] Howells, “Mark Twain: An Inquiry.” Pp. 167.

[xvi] Mark Twain’s Autobiography. 2 vols. Ed. Albert Bigelow Paine. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1924.. I: 220.

Suggested Further Readings

Aaron, Daniel. The Unwritten War: American Writers and the Civil War. New York: Knopf, 1972.

Ashland, Alexander. “ Navigating the Textual Currents of Reconstruction in Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi.” Mark Twain Annual, 22 (2024).

Bridgman, Richard. Traveling in Mark Twain. Berkeley: U of California P, 1987.

Cox, James M. Mark Twain: The Fate of Humor. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1966.

Cox, James M. “Life on the Mississippi Revisited.” The Mythologizing of Mark Twain, eds. Sara De Saussure Davis and Philip D. Beidler. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1984.

Goeke, Joseph. “Border Life on the Mississippi: Civil War Border Politics and Mark Twain’s Humor.” Studies in American Humor, 25 (2012).

Horowitz, Howard. By Law of Nature. New York: Oxford UP, 1991.

Howe, Lawrence. “Afterword,” Life on the Mississippi. New York: Oxford UP, 1996

Howe, Lawence. Mark Twain and the Novel: The Double-Cross of Authority. New York: Cambridge UP, 1997.

Kruse, Horst H. Mark Twain and “Life on the Mississippi.” Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1981.

McCammack, Brian. “Competence, Power, and the Nostalgic Romance of Piloting in Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi.” Southern Literary Journal, 38.2 (2006).

Pettit, Arthur G. Mark Twain and the South. Lexington: U of Kentucky P, 1974.

Weinstein, Cindy. The Literature of Labor, The Labor of Literature. New York, Cambridge UP, 1994.

About the Author

Lawrence Howe, Professor Emeritus of English in Film Studies at Roosevelt University, is a past editor of Studies in American Humor and author of Mark Twain and the Novel: The Double-Cross of Authority, and co-editor of Mark Twain and Money: Language, Capital, and Culture, and Refocusing Chaplin: A Screen Icon through a Critical Lens, as well as numerous articles on a wide range of topics in American studies. In 2014-15, he was the Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies in Denmark, and in 2020-2022 he was president of the Mark Twain Circle of America. He has enjoyed the generous support and recognition of the Center for Mark Twain Studies for more than a decade, including being honored with the Henry Nash Smith Award in 2022.

Professor Howe has participated in a number of CMTS events and given numerous lectures, including:

- Lawrence Howe, “Skewering Gilded Age Corruption: The Visual Satire of Thomas Nast” (October 12, 2024 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Lawrence Howe, “Mark Twain, Property, and Poetry” (May 31, 2023 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Lawrence Howe, “Scandal at Stormfield: Mark Twain’s ‘Ashcroft-Lyon Manuscript’” (June 3, 2020 – Online)

- Lawrence Howe, “Mark Twain and America’s Ownership Society” (October 17, 2012 – Quarry Farm Barn)