Jane Lampton “Jean” Clemens

Image Courtesy of the Mark Twain Archive, Elmira College, Elmira, NY.

Image courtesy of the Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, CT.

Image Courtesy of the Mark Twain Archive, Elmira College, Elmira, NY

Jane Lampton “Jean” Clemens was the fourth and final child of Samuel and Olivia (“Livy”) Langdon Clemens. Named after Sam’s mother, she was always called “Jean” by family and friends. Jean was born on July 26, 1880, at Quarry Farm, the Clemens’s summer home in Elmira, New York owned by Livy’s sister and brother-in-law Susan (“Aunt Sue”) and Theodore Crane. Though the youngest of the four Clemens children, she grew up as the third of their three daughters; their first-born, a son named Langdon, had died of diphtheria in June of 1872 when he was only 19 months old. Jean’s two sisters were Olivia, known as “Susy,” and Clara, nicknamed “Bay.” Born in 1872 and 1874 respectively, they were both several years older than Jean.

After her first few years, Jean led a somewhat separate life from her sisters, who were closer to each other not only in age but also in temperament, interests, and life experiences. As she grew older, her differences from her sisters became apparent. While they pursued writing, music, and singing – Susy was already writing her biography of her father, Papa, at the age of 13 and Clara was immersing herself in music, eventually becoming a professional singer – Jean was most drawn to nature and especially to animals. “I know a few people who love the country as I do, but not many,” she once reflected. “Most of my acquaintances are enthusiastic over the spring and summer months, but very few care much for it the year round…To me, it is all as fascinating as a book – more so, since I have never lost interest in it” (Paine, 1552-1553). Not surprisingly, then, Jean preferred from a young age to spend her time outdoors and with other creatures. Commenting on his daughters’ prospects when Susy was about 19, Clara about 17, and Jean about 11, their father joked, “We haven’t forecast Jean’s future yet, but think she is going to be a horse jockey and live in the stable” (Courtney, 85). Eventually, Jean joined the Humane Society and became what we today call an animal rights activist. In her father’s later years, she was able, through her own passion for that cause, to interest him in it and specifically in anti-vivisectionism, which led Twain to write such stories as “A Dog’s Tale” and “A Horse Tale.”

When she was 15, Jean was diagnosed with epilepsy. For the rest of her life, she suffered badly from the condition, which had no effective treatment at the time. Although she had some periods of remission, her chronic illness and unpredictable seizure episodes limited her life and social activities. She never married, had children, or developed a paid profession. She died at the age of 29 on Christmas Eve while living with her father at Stormfield, the mansion he had built in Redding, Connecticut. She was taking a bath after helping to decorate for the holidays and apparently had a seizure that led to either heart failure or asphyxiation. Her heartbroken father, who had already lost his oldest daughter Susy to spinal meningitis at the age of 24 and his beloved wife Livy to chronic illness at the age of 56, died himself four months later. (Clara then became the only surviving member of the immediate family.)

Childhood Years and European Travels

The entire family was delighted by Jean’s birth. Her father called her “the prettiest & perfectest little creature we have turned out yet” and wrote that “Susy & Bay could not worship it more if it were a cat” (Salsbury 119–20). Livy described Jean as “a wonderfully nice baby . . . a dear little thing” and “the fattest healthiest baby we have had” (letter to Mollie Clemens in Snedecor, 155-156). She wrote a friend that Jean “is a comfort to us all. She looks very much like her father and is very fond of him”( letter to Hattie J. Gerhardt in Snedecor, 158).

Like her sisters, Jean spent her early years dividing time with her family between their main residence in the Nook Farm neighborhood of Hartford, Connecticut, and Quarry Farm. Typically, they spent extended summers – often April to September – at the Farm, where Jean was free to roam outdoors and be near animals. Her father related how, at the age of 3, she delighted in watching the milking of cows.

She sits rapt and contented while David milks the three, making a remark now and then—always about the cows. The time passes slow and drearily for her attendant, but not for her—she could stand a week of it. When the milking is finished and “Blanche,” “Jean” and “the cross cow” turned into the adjoining little cow-lot, we have to set Jean on a shed in that lot, and stay by her half an hour till Elisa the German nurse comes to take her to bed. The cows merely stand there, amongst the ordure, which is dry or sloppy according to the weather, and do nothing—yet the mere sight of them is all-sufficient for Jean; she requires nothing more” (Twain, A Family Sketch 95b).

Clemens family at their Hartford House in 1884. From left to right: Susy Clemens, Sam Clemens, Jean Clemens, Olivia Clemens, and Clara Clemens.

Image courtesy of the Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, CT.

Image courtesy of the Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, CT.

Jean on the roof at Quarry Farm. Bim Pond (left) and Susan Crane (right).

Photo taken September 15, 1895. Photo courtesy of the Mark Twain Archive, Elmira College, Elmira, NY

Like her sisters, Jean was educated in her early years by her mother and private tutors. Later, when the family was living in Europe, she attended school.

The family’s Hartford-Elmira days came to an end when Jean was 11. The entire family departed for Europe to live more frugally in the face of Twain’s crippling debt from bad business investments. Until 1894, when they returned to North America so he could prepare for a world speaking tour, the Clemenses traveled through France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. During much of that time, Jean kept a detailed journal that showed how much of her education occurred during those years through travel.

Pursuits and Talents

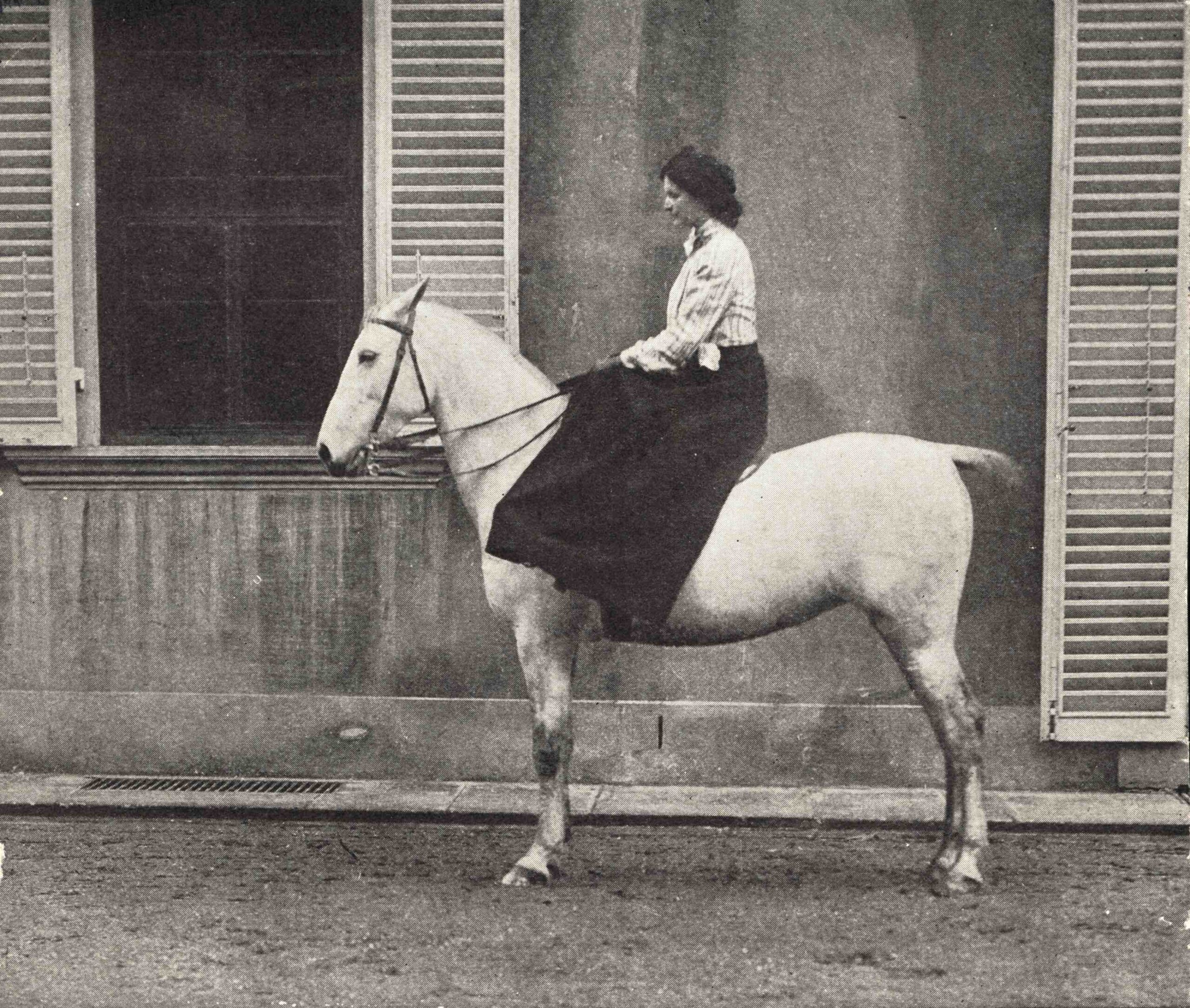

While some biographers have focused on how Jean’s epilepsy limited her life from adolescence onward – which was certainly the case – it is also true that she was something of a natural athlete. She liked to ski, ice-skate, and hike, and she played tennis and squash. After her diagnosis, when fresh air and exercise were recommended as part of her treatment – along with sedative medication and a controlled diet – she became “an accomplished and ardent horsewoman” (Simboli).

In addition, she was apparently the best linguist in the family. “Jean’s aptitude for languages was remarkable” (Salsbury, 318) and she ultimately became fluent in German and French, with a working knowledge of Italian. By the time she was 12, her father observed, “when she talks German, it is a German talking – manner and all; when she talks French she is French – gestures, shrugs, and all, and she is entirely at home in both tongues. She is getting a good start in Italian and will make it property presently” (qtd. in Wexler, 269-270).

In her later years, Jean also learned decorative wood carving, creating artistic glove boxes that she hoped one day to sell for an independent income.

Image courtesy of the Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, CT.

Invalidism and Final Controversy

The Clemenses sought various cures and treatments for Jean’s illness in England, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.S. Despite the stigma then attached to epilepsy, her mother Livy continually did her best to keep her youngest daughter involved in the social life of their family and friends, and Jean did participate actively as much as possible. Even so, she was not able to enjoy the same robust social life as her sisters, who frequently attended balls, dinners, performances, and other events. She frequently required constant supervision and was encouraged to maintain a quiet, calm lifestyle, which was then thought to be the best approach for epilepsy.

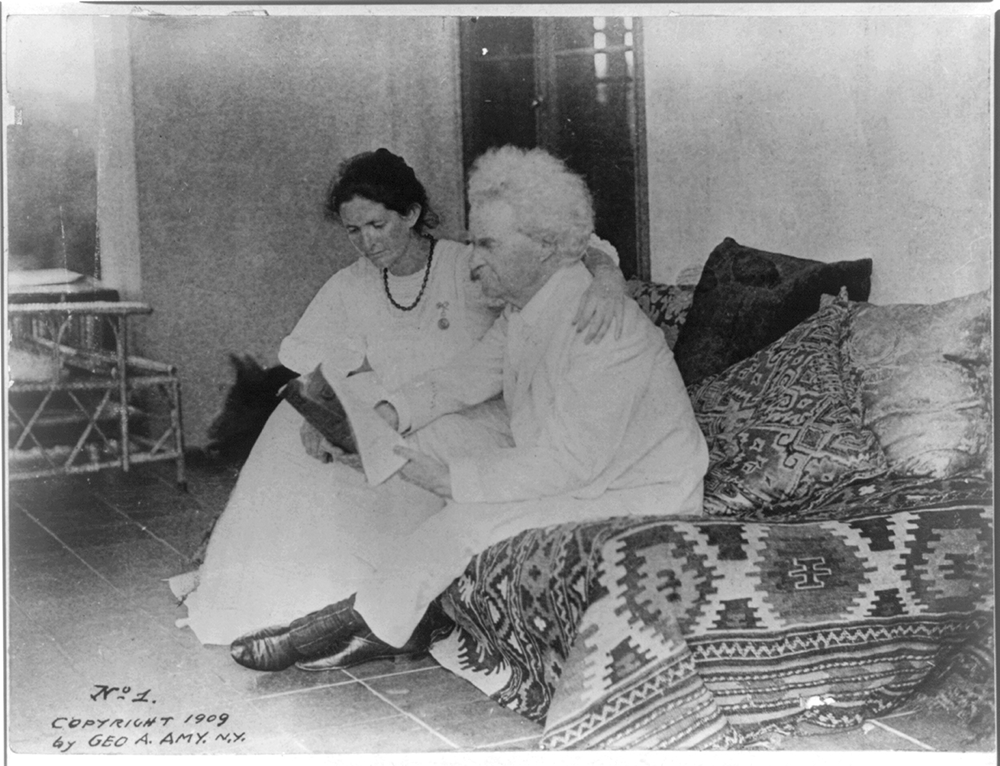

In 1904, when Jean was almost 24, her mother died. Beyond the family’s grief, the loss of Livy was especially consequential for Jean. After that, her life became more separate and eventually isolated. Her father, by then 68, was not able to provide the same level of care that Livy had, and her sister Clara, then almost 30, was grieving deeply as well as pursuing a singing career. It was left to Sam and his household staff to care for Jean, which did not go well. Although accounts of Jean’s behavior and interactions with household members vary, it seems clear that his secretary, Isabel Lyon, influenced him to institutionalize Jean. (Some scholars claim Lyon was scheming to marry Twain and took advantage of him financially.) In the fall of 1906, at the age of 26, Jean was sent for residential treatment to a sanitarium in Katonah, New York, some 45 miles from where Twain was then living in Greenwich Village. Despite Jean’s requests to return home, she remained there until April 1909, after her father had dismissed Lyon. He brought her back to Stormfield where, in their final time together, they enjoyed a reconciliation, with Jean serving as her father’s secretary.

Image courtesy of the Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, CT.

Her Father’s Final Tribute

In “The Death of Jean,” a touching tribute published as part of the collection “What is Man and Other Essays,” Twain reflected on his youngest daughter’s kindness and generosity. “There was never a kinder heart than Jean’s, he recalled,

From her childhood up she always spent the most of her allowance on charities of one kind and another…She was a loyal friend to all animals, and she loved them all, birds, beasts, and everything — even snakes — an inheritance from me. She knew all the birds: she was high up in that lore. She became a member of various humane societies when she was still a little girl— both here and abroad — and she remained an active member to the last. She founded two or three societies for the protection of animals, here and in Europe. (120)

Of his own deep pain at her death, he wrote with great sorrow, “Possibly I know now what the soldier feels when a bullet crashes through his heart” (“The Death of Jean,” 111).

Image courtesy of the Mark Twain House and Museum,

Hartford, CT.

Photograph of Jean Clemens and Mark Twain (1909).

Appeared in Philadelphia Inquirer (26 December 1909), 18.

Suggested Readings

Bauer, Philip. “For the Sake of Growth and Change: “My Inconsistent Look at the Life of Jean Clemens.” Paper, Ninth International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies, Elmira College, New York, August 4, 2022.

Courtney, Steve. “The Loveliest Home That Ever Was”: The Story of the Mark Twain House in Hartford. Garden City, NY: Dover Publications, 2011.

Paine, Albert Bigelow. Mark Twain: A Biography, Volume III. NY: Harper & Brothers, 1912.

Salsbury, Edith Colgate. Susy and Mark Twain. NY: Harper & Row, 1965.

Simboli, Raffaele. “Mark Twain from an Italian Point of View,” The Critic, June 1904. Qtd. on twainquotes.com.

Snedecor, Barbara E., ed. Gravity: Selected Letters of Olivia Langdon Clemens. Columbia: U Missouri P, 2023.

Trombley, Laura Skandera. “She Wanted to Kill: Jean Clemens and the Postictal Psychosis.” American Literary Realism, Spring 2005, V. 37, No. 3, 225-237.

Twain, Mark. A Family Sketch. In Benjamin Griffin, ed. A Family Sketch and Other Private Writings. Berkeley: U of California P, 2014

Twain, Mark. “The Death of Jean.” In What is Man and Other Essays. NY: Harper & Brothers, 1917.

Wexler, Dixon, ed. Mark Twain to Mrs. Fairbanks. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1949.

About Paula Harrington

Paula Harrington is Director Emerita of the Farnham Writers’ Center at Colby College, where she was also an Associate Professor of Writing and taught American Literature. She was a Fulbright Scholar in Paris, France, where she researched Mark Twain’s antipathy for the French. That work led to the book, Mark Twain & France: The Making of a New American Identity ( U. Missouri P, 2017), co-written with Ronald Jenn, Professor of Translation Studies at the University of Lille, France. Their work was shortlisted for the French Heritage Society Book Award and nominated for the Warren-Brooks Award for Outstanding Literary Criticism. In addition, Harrington wrote the blog Marking Twain in Paris, and she has published several articles on Twain’s work in the Mark Twain Annual and the French Review of American Studies. She was the Senior Researcher for the France-Berkeley Fund Grant project, The “French Marginalia” of Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc: Patriotism Without Borders (with Ronald Jenn, and Linda Morris). She has given talks on Twain in France at the universities of Sorbonne Paris Nord, Lille, Lyons, and Angers and the American Library in Paris, as well as at public libraries and bookstores in Maine, where she lives.

Dr. Harrington has participated in CMTS events and lectures, including:

- Paula Harrington,“The French Face of Twain” (May 14, 2014 – Quarry Farm Barn)

- Presentation of papers and chairing of panels at the International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies, held quadrennially at Elmira College and Quarry Farm.

Her lecture on Mark Twain and France at the American Library (19 April 2016) can be viewed below: